We all have surahs that affect us in particular ways. Chapters of the Qur’an that mean something personal. Specific verses, even. Did you know the word for verse, in our tradition — ayah — actually means “sign”? A South Asian philosopher, Muhammad Iqbal, once said there’s three signs of God around us. One of these is the natural world; the rhythms of the sun, the moon and the stars. The incredible complexity and beauty of what’s out there, big and small, should remind us of God, which is why sitting in and contemplating nature is such a profound experience.

By the way: There’s a great book about this by Malik Badri (you can read the PDF version of the book here, made available by the publisher).

Another sign, Iqbal said, is history itself: The ways of people before us are worth studying. There were lots of decent people whose legacy shines long after they’re gone. Conversely, there are a lot of vain, arrogant people, who think they’re on top of the world, and become instead abject lessons in the moral logic of God’s world. Whether that’s Bashar al-Assad, ignominiously fleeing for his life or Presidents who start wars on false pretenses and drape “Mission: Accomplished” banners before the mission’s even really underway, not to mention nobody knows what the mission is.

I’ve been thinking about that a lot lately, watching Donald Trump’s inauguration and subsequent flurry of executive activity. I’m not here to pick sides between right or left, a principle I extend to my halaqas; I’d rather that we teach our kids to ask better questions and explore a range of possibilities and then make up their minds.

In fact, in recent years, I’ve become much more open to hearing from conservative and progressive voices alike without reflexively identifying with either side.

But there are certain principles, certain truths, certain frames that don’t fade, that are bigger than party and country. Pride, for one, goeth before the fall, which is in fact from the Bible (Proverbs 16:18): Pride goes before destruction and a haughty spirit before a fall. There’s an analogous German saying: “You can march triumphantly into your grave.” What does that have to do with the 89th chapter of the Qur’an?

And what does any of this have to do with the halaqa?

Know What Happened

(So You Know If It Should Happen Again)

In the first two weeks of the high school halaqa, we’ve been zeroing in on the precise moment when the Prophet Muhammad, peace be upon him, passes away, followed by the debates and divisions that emerge in and because of his absence. While I come at this history from a Sunni perspective, I do not believe the nomination of Abu Bakr, may God be pleased with him, was obligatory in the way that say fajr prayers or fasting in Ramadan might be (depending on your age and health)… though, of course, that hardly means his selection as Caliph wasn’t a wise, reasonable and profound one.

Nevertheless, each of the four Caliphs was a formidable person; there were others, too, who might have held that office well. At that moment and in hindsight (for many of us), Abu Bakr was if not the only choice, then among the most if not the most obvious choice.1 In coming weeks, we’ll unpack how early Sunni Muslims — before there was even such a term as “Sunni” — tried to locate authority in a Caliph who was first among equals, a pious follower of the Prophet (S), until the Umayyad usurpation and especially the rise of Yazid, led to a period of great disillusionment.

Over subsequent decades, the community at large began to locate authority elsewhere. However, that didn’t happen overnight.

It took years. Decades. To find a new equilibrium.

These included schools of thought. Practices of purification and contemplation. Fraternal orders. What you can call madhahib, tazkiyya, tafakkur, and tasawwuf. Realizations of what it meant to follow the sunnah (path) of the beloved Prophet (S) and hold to community, a kind of checks-and-balances approach that can move achingly slowly, which can be really frustrating at times, but ultimately reflects a deep wisdom: By moving gradually, we put the brakes on people of charisma and presence who are found in every time, who come to take more than they deserve, and sometimes lead whole people astray, even into disaster.

Of course, we haven’t gotten to the Umayyads yet… all of that will be in the weeks and months to come, though you should know why we’re studying this history. Not just so that we know what happened (though we should). But so that we have a sense of what happened before us, so that we can see red flags, so that we can appreciate how people before us might have acted—and what resulted.

Because Iqbal was right about history: It is a sign of God. The world around us is a sign from God. What do we do with these signs?

NPR: Chris Pizzello/AP

It’s a Little Too Late For That

This coming week, I’d like my students to read from Imam al-Ghazali’s The Remembrance of Death and the Afterlife, specifically the section on the last hours in the life of our Prophet (S). We should repeatedly return to how great people die, because we cannot have beautiful, meaningful ends if we did not have beautiful, meaningful lives; few people are so blessed as to chance on a last-minute burst of divine favor without laying the groundwork long before. Just like you shouldn’t expect to retire let alone age well if you haven’t put some effort into it. I’d like them to read certain moments again and again and again, literally and abstractly.

I’d also like them to reflect on what Abu Bakr, may God be pleased with him, says when he becomes Caliph.

At his inauguration, if you will.

The last few verses of Surah Fajr, the 89th chapter of the Qur’an, describe God speaking to a certain kind of soul (al-nafs al-mutma’innah)—one not just content with and at peace with God, but one whom God Himself likewise favors. It’s a reciprocal relationship. A two-way street, eternally speaking. God invites this soul into His garden. The serene description follows after a far more painful passage (verses 17-26), the contrast between which is of course intentional and all the more affecting because of the jarring juxtaposition.

In verses 17-26, it’s not just what God is saying, but how; the rhyme, the fierce urgency, the melodic thunder of it all, the way in which a handful of words don’t just describe but pulverize your sense of self, security, and priority, the meaning magnified by the very limited number of words. If you’ve studied Arabic, you feel these verses in the pits of your stomach—if you hear the Arabic, you’ll get the same urgent panic and terrified sense of helplessness and paralysis (verses 17-26 at 1:18-2:06).

Here I attempt a translation:

But no!—you don’t feed the orphan

and you don’t urge each other to feed the poor

and you eat up the wealth (inheritance) of others with greedy abandon

and you love wealth with a love that rages

Then, suddenly, God cuts His own description off with a thundering “enough!”

Enough! When the earth is pounded to powder (crushed, over and over)

and your Lord comes to judge, with rank upon rank of the angels

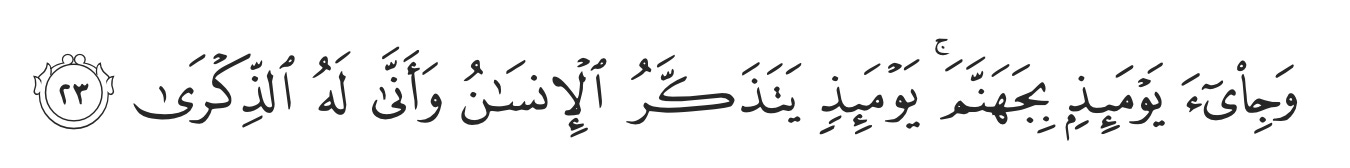

and Hell is brought forth: on that day, every person will remember. But what is the point of remembering then?

That last part of the above verse, “wa anna lahu dhikrah?”—is usually translated as a polite question: “But what is the point of remembering then?” But when I hear it, I hear it with a caustic burn. Right after God mentions hell, we are told it’s likely too late for a lot of us, who will only wake up way after the alarms had long since fell silent. If this were a person like me, on that day, realizing what I’d wasted my time on, I’d put it a little differently.

What the hell point is there in remembering now?

An “ayah” is a sign. Remembering here is dhikr, the same word we use for the recollection of God during the day, for example after prayers.

Drill, Habibi, Drill!

A recent Ezra Klein op-ed for the New York Times points out that the vibes following Trump’s victory don’t correlate with the margin of victory; this feels more momentous than the math alone suggests. He’s right. Democrats are beyond reeling. The old liberal order is faded. For as aged and infirm as Biden appeared physically, he had well before disintegrated morally—as his policy choices establish.

Had we looked to a man so hollow, so far removed from any sense of right and wrong, to right this ship, we would be dismayed today.

Had we seen on the other hand how far gone he was, we’d have known: We are in one of those intermediary phases; those who adore and revere Trump are front and center and will dictate much, certainly now, and perhaps for years to come; there will eventually be a response and a rebuttal, but the articulation of that rebuttal, the formation of a critique, and its realization, takes time.

We cannot force that cycle and cannot allow that cycle to exhaust us, either. In a way, this isn’t so different from the period the earliest Muslims faced after the martyrdoms of ‘Uthman and then ‘Ali and his son, the Prophet’s beloved grandson, Husayn, may God be pleased with them and ennoble their faces. People were left reeling. A system they might have believed in hadn’t just failed them, but appalled them.

What then? What now?

That’s hardly an exact analogy on so many counts, but there is a kind of parallel all the same. Many truths many Americans relied on have been revealed, in recent years, to be so much smoke and so many mirrors. Does that mean we just go along with what comes next? When Abu Bakr came to power, he told his community that, if they worshipped Muhammad (S), well, the Prophet was now passed on.

But if you worship God, he said, well then God lives and cannot die.

We do not go along with what seems seductive, or even inevitable, and believe me, few things feel as seductive as an idea or a politician whose time seems to have come, unless what we see accords with our values, our beliefs, our principles.

Unless we know our values, our beliefs, our principles.

When Abu Bakr took the Caliphate, he told people that he should be followed only so long as he followed God and His Prophet; otherwise, he demanded his people correct him. He all but admitted he could get it wrong and that there was a power over him.

When ‘Umar was Caliph, he would think about the possibility of an animal dying of thirst in the lands under his control and tremble for fear he would have to answer. The same ‘Umar, the mighty warrior, the big strong man, the one who wasn’t afraid to call anyone out, was worried about animals.

When a famine hit the Caliphate, in solidarity with his people he refused to eat meat. How can I enjoy wealth, he broadcast, when my people are struggling?

We can find similar examples of generosity, humility and dignity, of honor and piety, in the lives of ‘Uthman and ‘Ali, of course, whose wisdom included his warning: People are asleep and, when they die, they wake up.

While California is on fire, Trump calls for more gasoline cars. Drill, baby, drill! While the South is hit by a blizzard, and we lived through the hottest year ever, he announces there should be no more limits on our industries. Has a man with an unchecked ego ever led any people anywhere good?

After years of Americans fighting and dying and funding wars, wars that did not enhance our security, wars that bankrupted and exhausted us, after years of Americans asking for peace and an investment in us, he wants to unravel the world order by threatening friends and allies, by announcing he’ll go back on our country’s commitments, because who is anyone to check him?

Man Plans, God Plans, Lesson Plans

This is a potent moment in our country’s history. But it is hardly a moment without precedent. Many countries have suffered delusions of gold-plated grandeur. In our halaqas, we spend time on the lessons of history and how these tell us what kind of people to be. Not afraid to speak up for what we believe in. Not hesitant to seize opportunities or imagine the future. But remembering always that the believer who is not conscious of his shortcomings and dependency is not much of a believer.

Let alone a leader.

We may not know yet how to articulate what comes next. We have work to do, as Americans, to develop a vision of democracy that meets the moment now and the moments ahead. We know that work can take years. But many people, including our ancestors, had been in moments like this. They persevered. They did what had to be done. They made their contributions. Nobody guaranteed us easy lives. But that also means we have purposeful lives.

We should be equipping our kids with the skills, the character, and the resilience that this moment needs.

What does that mean tangibly and practically?

First, we should teach our kids history. They shouldn’t just know what happened in Islamic and American history, including American Muslim histories, but they should be able to (i) draw lessons from history, (ii) compare time periods across histories, and (iii) know how to reference past events to articulate future priorities.

Second, this doesn’t mean knowing the minutiae of history so much as knowing broader outlines, trends, patterns and lessons. There’s a reason we study the lives of great people—these warn us, inspire us, console us, and deepen us, turning us from ephemeral reflections of what is to active contributors to what can be and should be.

Third, they should be able to explore the idea that there are different explanations for events, that these causes and effects can be studied and contrasted, and that this kind of skill is required to successfully make choices about their future priorities.

Finally, encourage your kids to pursue open-ended reflections on and debates about historical events. Teach them to think critically, to learn how to develop and debate with each other, and to develop more refined arguments.

Here’s a few examples I’ll unpack in future posts.

In last week’s class, I asked them questions like: Should there have been a Caliph at all? Why might there have been so much infighting? And in weeks to come, I’ll ask are there structural reasons for why we see so much instability in key periods? What does that mean for us now, in a time when the world is rapidly changing? And how do we build community when we know, from history, we aren’t always (or really ever) going to agree on some of the biggest questions of all? A halaqa without questions isn’t a halaqa at all.

I do my best to charitably include Shi’a perspectives, with two caveats.

First, this is of course a class not just about religion, but a religious class, and so I do lean in certain directions (while I also encourage them to think about the questions and motivations at work, not just reflexively insisting on one possibility.) Second, I do also make clear that I don’t know nearly enough about Shi’a perspectives to do these fair justice and am always trying to read up and share more.

do you have any recommendations for Islamic history books? and do you do any online halaqas discussing it? it all seems very interesting :)