Will There Ever Be A Muslim Generation That Doesn't Know Genocide?

Still wondering where the ummah is

I can’t remember her name. She was a quiet older woman who opened her home, her kitchen and her heart to us. I do remember why I look so downcast in the picture, though. Over a lunch she cooked for our group, she told us how the men in her family had been brutally killed, including her husband and son, some of the over eight thousand boys and men murdered in the Srebrenica massacre.

We were North American Muslims, almost none of whom had ever been to Eastern Europe. She invited us to ask questions. But when someone asked if she knew who the killers were, I flinched. That didn’t feel like an appropriate ask. She didn’t hesitate, however. Her next-door neighbor, about her age, was one. She’d chosen to live for years beside a man who enthusiastically helped to wipe out her family.

She’d refused to move. She would not concede to the campaign to cleanse Bosnia of its Muslims. I cannot forget that home. That hurt. That courage.

Twenty-nine years later, we must remember. We remember against all the people who lie, claiming Islamophobia is harmless, victimless, even “imaginary.” In my own lifetime—and I’m not that old—tens of thousands of Europeans have been murdered because they were Muslim, even as, with straight faces, practical fascists scream and clamor and run for office claiming Islam doesn’t belong in the West.

But there have been Muslims in Europe, most of them the descendants of Europeans who voluntarily converted to Islam centuries ago, longer than Protestantism has existed in Europe (or anywhere). If Islam doesn’t belong in Europe, why does Lutheranism? (To be clear, both do.) There have been Muslims living continuously in the Americas since well before Donald Trump’s mother immigrated in 1930.

These absurd, ahistorical arguments would be embarrassing if they did not occasionally lead to horrific outbursts of violence.

Or excuse us from if not encourage our complicity in such brutality.

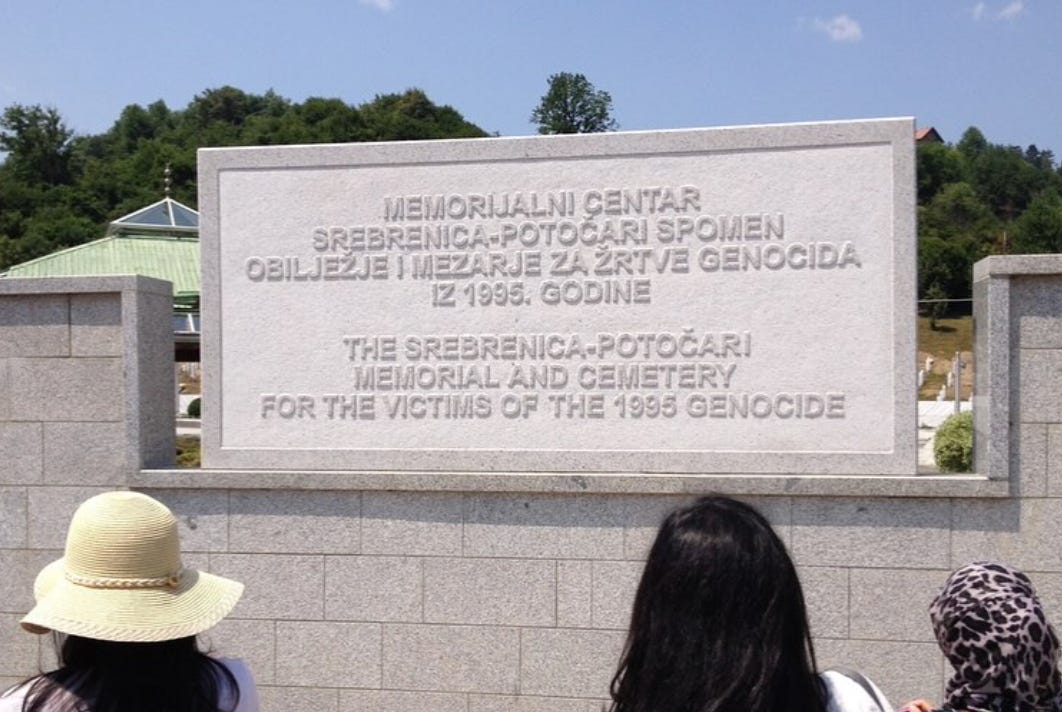

That July of 2012, I was leading a tour I’d spent the previous year designing. I’d already built two trips to southern Spain, where we explored the causes and consequences of the Reconquista, the Iberian Peninsula cleansed of its indigenous Muslims (and Jews)—based on the lie that Islam and Judaism were foreign to Spain. Note: By 1000, a majority of Spaniards had voluntarily become Muslim.

As late as the 19th century, Eastern Europe probably had a plurality of Muslims, if not a slight majority. Then there was a Balkan Reconquista, which we mostly know very little about, expelling or eradicating huge Muslim communities in Bulgaria, in Romania, in Bosnia—and so we created a tour through the Balkans, with the intention of weaving past, present, and future together.

That was how we found ourselves there in July, in Bosnia (Sarajevo, Mostar, and Srebrenica) and then Istanbul, Islam, discovering connections across history and their implications for us now. I can’t underscore this enough: You can’t imagine the impact on Muslims, especially young Muslims, to see Islam lived beyond their horizons. To know your faith is global is one thing.

To see that cosmopolitanism, and even to know that there are different, competing kinds of cosmopolitanism, is profoundly transformative.

While these tours (including upcoming tours to Spain, the Balkans and beyond this year and in 2025) make plain Islam has taken deep root in all kinds of places, these tours also refuse debilitating, wistful nostalgia. Whether or not the world was better in the past is potentially impossible to answer; after all, on what metrics? But that is also a spiritually dangerous question, too.

Because God chose us to live where and when we are, not where or when we wished we would. Does God know best or do you?

Unleash Your Inner Ummah

We study the past for the same reason Allah SWT (God, Glorified and Exalted) references history throughout His Qur’an: history is a source of knowledge, a means by which we become more fully and profoundly human. Education shouldn’t be facts divorced from outcomes, means divided from ends. Education is rather the bridge that takes us from understanding who we are to pursuing who we can and must be.

Conversely, nostalgia usually doesn’t ask us to work on ourselves or ask much of us at all. Worse, sometimes nostalgia propels us to take actions that might harm us or harm others. In the Islamic conception, a secular success predicated on a moral outrage is not in fact an achievement. It could be our doom. We may not feel the consequences in this life, but we will have to answer in the world-to-come.

On that visit to Srebrenica, which had been my first to Srebrenica thus far, we were guided through a factory where many of these boys and men (aged 12-74) were held, then killed. Now, this was a tour I was in charge of, though because the participants had a local guide with them at this juncture, I hung back, anticipating that we would reconvene at the sprawling cemetery, to pray, to ponder, to talk.

But before I knew what had happened, I found myself a long distance away. I was so overwhelmed and shocked by the raw evil of what had happened that I must have left at some point, unplanned and unconsciously: I can’t remember the path I took out. Eventually I bumped into a young Turkish grad student, part of the tour, and in a glance we understood that we’d reacted similarly.

We’d fled. But there was no way to flee, not really. Not actually. Or ethically.

I knew then that I’d keep bringing people to places such as these—to see the wounds, yes. But also to see the warmth. To build connections, to cultivate appreciation, to become the solidarity we so desperately seek. In crisis, we often ask, where is the ummah? Except to paraphrase the first Catholic President: Ask not what your ummah can do for you. Ask what you’re doing for your ummah.

Rather than wondering where the ummah is, consider where you are. Because God put you where and when you are for a reason.

And made you who and how you are for a reason.

God gave me a love for travel, a passion for history, a zeal for languages, and a comfort with uncertainty (call it an appreciation of adventure and discovery). I enjoy teaching and I’m pretty good at it, too. Doesn’t that mean I should use that in some positive, purposeful direction? There were few Muslims I knew growing up who’d have been inclined to produce such programs.

But so many who wanted to connect to their history, to learn beyond headlines, stereotypes, and assumptions. If we want an ummah, in other words, we must work to build it, every day, just as everything else we do.

When I was in high school in the 1990s, the Bosnian genocide erupted. The occupation of Palestine was of course still ongoing. Kashmir continued to suffer. In my life, we’ve seen additional disasters befalling Muslims—Syria. Libya. Sudan. Iraq. Afghanistan. Chechnya. Kosovo. For our kids, the war on Gaza leaves an emotional, spiritual, and existential scar not dissimilar from Srebrenica.

Each successive generation of Muslims doesn’t just grow up with memories of ethnic cleansings and recent genocides. They don’t just hear warnings of the dangers of unchecked bias and bigotry. They see ongoing, eliminationist campaigns, viciously eradicating people who believe what they believe, pray like they pray, fast like they fast, in ever more visceral ways.

I’d be lying if I said that didn’t infuriate me. Will there ever be a generation for which this isn’t the case? I’d be lying if I said I didn’t wonder what this does to an ummah to keep seeing this happening, with people of power and influence, who could do something, instead choosing to do nothing, if not making it worse. But I’d be complicit if I didn’t do something, too.

When we feel let down by ummah, part of the problem is we’re expecting an abstraction to translate into outcomes without effort. There’s nothing wrong with wanting a more prosperous and potent ummah, unless of course you expect that to magically become real. Rather, we are individuals in communities. If we strengthen individuals, we strengthen the communities we concretely live in and experience.

If we energize those communities, and empower them to act collaboratively with nearby communities, though, we bring about what right now we just yearn for. That might just be a generational project. But it’s hardly impossible.

Even as I’m asking us to focus granularly and locally, remember that our sentiments are shared by tens of millions. If we learn and teach, and learn from and teach each other, we can scale change in surprising ways. Put it this way: If one masjid builds an endowment model that creates financial independence, and ten others borrow that with success, a small change has become a huge one.

As long as we rid ourselves of this un-Muslim, zero-sum mentality.

That’s part of why I’m pouring so much time and energy into these tours and experiences. While it’s one thing to say I’m against nostalgia, I must also say what I’m for. When we went to Bosnia in 2012, we went to Srebrenica and met survivors. We also met Bosnian entrepreneurs who talked about investment opportunities. We met educators who explored what it meant to build Muslim life in a Western country.

We found common ground between North American and Eastern European Muslims.

We did this so the more resourced Muslims among us could consider opportunities to invest, create jobs, grow businesses, and change trajectories. And at the same time, we offered younger Muslims tangible opportunities to begin to cultivate a global consciousness, which I am confident will continue to bear fruit in years to come, in ways we can’t imagine. (One of the reasons why we offered some financial assistance.)

Islam Defined

It would be absurd not to talk to young Muslims about Islamophobia. But what would happen to us if we reduced our identity to tragedy? Not only is that untoward, and maybe even ultimately ungrateful to God, but that would mean an identity that keeps us from why we’re even here in the first place. After all, God chose when, how, and where we entered this world.

We answer to God for what we do with that. That means putting God first, not party, ideology, class, self-interest, nationality, ethnicity, even ummah. Otherwise we might become so consumed by injustice that we would be blind to wrongs we might commit, or even use injustice to excuse or propel injustice against others. Those who seek to eliminate a people fail to understand the nature of reality.

For nobody ever really dies. And more importantly nobody escapes judgment.

So please talk to your kids about what’s going on in the world. If there are events in your area about Bosnia, for example, take them. Seize every opportunity you can to empower and educate . Even by visiting a masjid that’s home to a different ethnic group, you’re broadening their horizons. Education doesn’t have to mean talking at them. The best education is exposure and immersion.

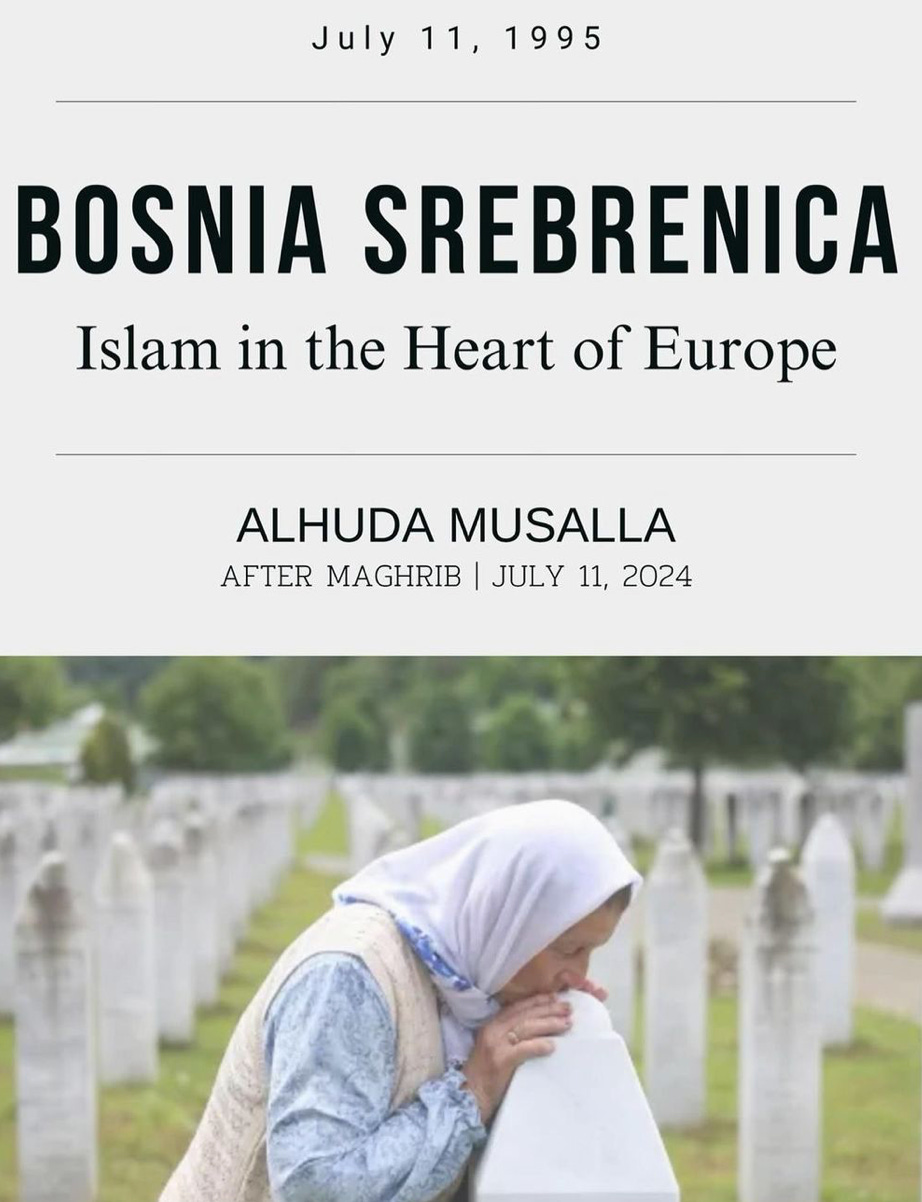

If they see you care, they’ll care. If they see differences, they’ll be inclined to organically and autonomously reflect on these. If they get context, they’ll learn how to think critically and creatively. (On which note, in Fishers, Indiana, a community member will be talking about Srebrenica after Maghreb [sunset] prayers in the Al-Huda Mosque’s musalla)—

That kind of education must be pursued such that we don’t create communities paralyzed by fear or despairing of God. Equally, we don’t want to create a community that believes a person’s claimed identity is all that matters. Even as there are many instances in which Muslims suffer shocking violence, we should not fear to point out when Muslims commit injustices.

Otherwise do we mean to say we’ll never talk about Sudan? Or Libya?

What about the Yezidis?

In age-appropriate ways, we have to always insert nuance, encourage our kids and our students to ask questions, and insist on human complexity, not to discourage each other from lives of purpose, but to remind each other that if we seek only to change others and never question ourselves (individually and collectively), we’ve missed the point. For the world changes faster than we think.

In my lifetime I have seen some Muslim-majority countries become fabulously wealthy and prosperous, in ways my parents’ generation would have scarcely believed possible. To what end? Some of these seem to have pursued such gains at the price of any conscience. Precisely when they should be thoughtfully leveraging their power to bring about more moral outcomes, they are entirely absent, if not painfully complicit.

Or for Americans like me, we can consider the cautionary tale of Joe Biden.

Here’s a man who wanted to be President for much of his life. And in the end, he got what he wanted. But what did he do with that power?

Anti-Genocide Joe

In the 1990s, during the genocide in the Balkans, then-Senator Biden was one of the few senior American officials who wanted our country to intervene. (Grotesquely, we were not bystanders in that conflict, but enforcing an arms embargo against Bosniaks—we not only wouldn’t help Muslims defend themselves from genocide, but more than that, we prevented them from defending themselves.)

President Biden was on the right side of that. While there’s a lot to question about America’s approach, eventually we did intervene, which complicates the crude idea that America is somehow preternaturally opposed to Muslims. That’s inaccurate, unhelpful, and unfair. Nevertheless, the Joe Biden who advocated for Bosniaks, and later Kosovo’s Albanians, is no longer with us.

Some three decades later, he’s emphatically and egregiously on the wrong side of things. He is complicit, and we as Americans are complicit, in the latest chapter of the nakba. He could have taken our American power, influence, and reach, in order to push for a real, meaningful, and lasting peace. He could have at least refused our weapons and resources in Israel’s war against Gazans and Palestinians.

Instead he has been backing the bombardment at almost every step.

These days, we hear a lot of talk about President Biden’s cognitive deterioration. For many of us, that kind of aging may well be inevitable. Death isn’t the worst thing that can happen to us, though. It’s inevitable, after all—a part of life. What’s worse? Somewhere along the way, President Biden morally deteriorated. His moral compass failed him, utterly and shockingly.

In every halaqa, no matter what topic, we start with praising God and the blessed Prophet. In part to remind us that we are not the North Star of our lives. That we can be wrong. That we will be wrong. In every prayer we make, we should seek forgiveness, for we are all flawed, we all make mistakes, and we can and will all err. That doesn’t mean we don’t have to act.

We should encourage our kids to be engaged!

When you talk about Bosnia and Srebrenica, about Palestine and Rafah, about Kashmir and Srinagar, about any injustice anywhere, ask your students.

What is our responsibility? Are we guilty of complicity? How can we do better? And bring history to bear, too—did others attempt to help? Did they improve the situation or worsen it? The more you can unleash their creativity, energy, and agency, the better. Find the causes they connect to, give them resources and insights you have access to, and let the conversation continue.

But we should enrich our engagement with humility. Reminding us to seek guidance from God, and strength from God, to constantly be open to learning, to listening to others, to challenging ourselves and being challenged.

May God give us the strength and courage to stand for what is right and against what is wrong, if even against ourselves. May He empower our communities, our countries, and our ummah, in the best of ways. May He save us from oppression.

May we never suffer oppression and may we never ourselves become oppressors.

If you’re interested in learning more about Islam in Eastern Europe, see this 2022 Sunday Schooled interview with Professor Leyla Azmi-Erdogdular.

In the near future, I’ll also be interviewing scholars and highlighting more resources. If you’re interested in future trips I’ll be leading, please subscribe—while our November 2024 trip now has a waitlist, details of upcoming trips will be shared here.