Should I Really Watch The Great Muslim American Road Trip?

And also: Atheism, Islam, and A Room of One's Own in Madison, Wisconsin.

Happy Friday, all: It’s three Eids in two days!

In the Islamic tradition, every Friday is its own Eid, a holiday of a sort (and in what is a bigger deal, it’s also the enormously significant Day of ‘Arafah); meanwhile, tomorrow, Saturday, July 9th, is Eid al-Adha, the most major holiday of the Muslim calendar, the Feast of the Sacrifice. On that day, we honor the immense sacrifices of our spiritual ancestors, Hajar, Isma’il, and Ibrahim (Hagar, Ishmael, and Abraham), may God be pleased with them, honor them, and give us the chance to join with them in the afterlife. This Eid marks among other things the conclusion of hajj.

The rebirth of our spiritual selves.

So for today’s Substack I have a special gift—an interview with Daniel Tutt, Director of Programs and Producer at Unity Productions Foundation (which has roots in southwest Ohio, if you didn’t know—and I didn’t.) He’ll share with us more about their latest production, a fascinating three-part documentary dropping now, The Great Muslim American Road Trip. It’s a journey along historic Route 66 with co-hosts Mona Haydar and Sebastian Robbins, a long drive and deep dive into the past and present of Muslim America. The centuries and centuries of history we should all know about.

And for those reasons—among many others—it deserves to be watched and shared, talked about and engaged.

American Islam is such a fascinating, diverse, curious, and confounding experience, which all the same we simply just don’t know enough about, neither those who belong to these communities nor who live alongside them. For kids especially that value can’t be underestimated: In a talk I recently heard by Mike Cosper, the force behind the fantastic podcast The Rise and Fall of Mars Hill (for adults for sure—but for adults of all faiths), he made this beautiful point.

Far more eloquently than I could, but I’ll try to reproduce it…

Cosper said that a good life requires that we know where we come from and what we can be, a sense of past and placement to ground us, and a view of a distant horizon meaningful enough that can inspire us to try to fly. The past, in other words, and the future. Without these, there is no present. So try to bring your friends, family, and community together to watch Road Trip!

But though that’s a lot, that’s not all.

Alongside this great interview about a great series, which I hope we all watch (as families—it’s safe for kids and a great inspiration to some immensely valuable conversations), I’ve included a link to a recent podcast appearance, on The Wisdom of Crowds, and information about my next book reading, this coming Monday evening at an independent spot in Madison, Wisconsin, A Room of One’s Own.

Route 786: Going on the Great Muslim American Road Trip

Dr. Daniel Tutt was incredibly kind and gracious in answering all the questions posed to him. Unfortunately, this interview had to be edited for space, but I kept what I believe and hope communicate and capture Daniel’s core points. Not only is his perspective quite valuable, but I would encourage you to share these answers with young folks interested in a life of storytelling—his experience and journey is in that regard rather unique and immensely significant.

Sunday Schooled: It’d would be great to understand how a series like this takes shape: How do you decide what to tell, to show, and what format to convey your story in?

With all our films at Unity Productions Foundation, we begin by formulating the big idea: what is going to connect with people and how does the story resonate with the current moment or zeitgeist? This is a careful process which is really spearheaded by Alex Kronemer on our team. I play the role of ensuring that the story is grounded in good research and historical knowledge informed by scholars and community leaders. So, I begin by reading many books on the topic and go diving for cool ideas. Then I interview a couple of dozen people on the topic, transcribe those interviews, study them carefully and then put together the backbone of a script from them.

With The Great Muslim American Road Trip, we began by reaching out to leading scholars and thinkers on the topic of Muslims in American history in general: what are the hidden stories, the forgotten tales? From these conversations we discovered several stories, historical vignettes, and ways to frame the idea of a road trip. This part of the filmmaking experience, what is called research and development, is always a lot of fun. You hear so many interesting ideas and then must narrow down to decide amongst them.

My colleague Alex had the idea of doing a road trip themed show and the idea of basing it around America’s “Mother Road” Route 66 made a lot of sense because if you could show that Muslims shaped the iconic American culture that grew up around this historic route, you could show that Muslims really are part and parcel of American history. It just so happened that PBS is taking an interest in shows that spotlight the US “Heartland” – so the program was met with a lot of enthusiasm from PBS executives.

I think what makes the program a success is that it combines a few key ingredients: it is hosted by two young Millennial age Muslims who are hip and interesting themselves: Sebastian is a white convert with a very sweet and genuine vibe and Mona is an Arab American hip-hop artist who is hilarious and full of zest. They bring a lot of chemistry and honesty to the film.

With these hosts we are primed to embark on a discovery journey of the Muslim community as it is today in the various small towns they travel to along Route 66. We also discover and unearth several historical vignettes about Muslims stretching back to the pre-Revolutionary period. I remember making a list of a few dozen forgotten stories, many of which could not be included in the film due to time and geographical location, but what we did include was very impressive in my view.

While I loved Road Trip, and found myself amused, intrigued, and engaged, one of my first thoughts (and maybe this is because I live in a multigenerational household) is that it might have worked differently if this was the story of a family, even a few generations of a family (from grandparents to grandkids), instead of a couple. I find that with teenagers, it’s hard to get them engaged if the people telling the story don’t immediately connect to their experiences.

How did you decide on who to make the focus of the story?

I think that's a great point, and I agree that people really tend to identify with likeness in storytelling, especially in contemporary media. When it comes to storytelling about American Muslims, it’s impossible to narrow down a common likeness of age, race, ethnicity, etc., that can stand-in for the community or do the job of representing American Muslims. To even suggest that there would be a common Muslim representative would never work. There is, therefore, really no limit to overcoming the stereotypes and boxes that Muslimness and Islam are placed into. This is the heart of telling Muslim stories: how to capture a radical diversity while at the same time capturing all its human complexity.

On the question of the multigenerational theme, I agree that it is important to make films that spotlight the multigenerational theme. This is important because of the significant divergence in worldview that young Muslims tend to have with their parents, a divergence that is of course not unique to Muslims by any means. And I totally agree that a story that can capture the inner workings of a Muslim American family would be important. Perhaps that is the work of fictional storytelling, feature films and TV series and not documentaries?

The Great Muslim American Road Trip is a quintessentially American story—in fact, your hosts, the road trippers themselves, even quote from Jack Kerouac, driving across and diving into the history of Islam in the United States (and, as we learn, before the United States!) But there’s so much story to tell there. How did you decide what to include and what not to include?

We had so many stories and vignettes to choose from and we had to limit it to the people and landmarks connected to Route 66. One story that I really wanted to discuss is the first all-purpose mosque built in the United States, which was located at the Ford Motor plant outside Detroit and built in 1922. Today the motor plant is gone thanks to deindustrialization but if you can believe it the community that lives near where the plant was is 40% Muslim! The State Department is wrong to identify the first mosque in Cedar Rapids, Iowa.

The Ford Motor plant mosque is far more interesting: there were South Asians, Ahmadi Muslims, Arabs, and many African Americans who had migrated North for work. I also wanted to do something on Sapelo Island and the Gullah Geechee people and the fascinating story of Bilali Muhammad who established a code of Muslim ethics and law for the enslaved people on the island. These stories were not proximal to Route 66 so they could not be included. But there are so many of these sorts of forgotten stories that I just love.

A big focus of the film series is that we wanted to balance the tragic with the more optimistic. So, for example, when we reach Tulsa, Oklahoma, we knew that it would be important to talk about the Tulsa race riot in the early 20th century because the community has been very engaged in reconciliation and justice around this tragic event. And Muslims in Tulsa have been involved in this work. We also combine with this story the more uplifting story about the history of black Muslim jazz musicians and the incredible number of Muslims who were jazz musicians.

We compiled what I think is the most comprehensive list of Muslim jazz musicians that has ever been compiled and we count 89 in total. We owe this research to Nathan Lean who is currently writing his Ph.D. on Muslim jazz musicians. I discovered the story of Hadj Ali, the Arab Muslim camel driver who was hired by the US Army to help forge the route of what would become Route 66.

All these ideas could not be included in the film, but they give you a glimpse into what sort of things we discovered in making the film and learning about Muslim history. There are so many vignettes like this! It is important to note that many of the encounters in the film were also chance encounters that happen spontaneously such as the encounter that we had with the break dancer in Las Vegas, who happen to be Muslim. Other encounters that were with Muslim communities as they are today, from the youth Muslim science team in Albuquerque to the prisoner reentry experience in Las Vegas, to the Bosnian community in Saint Louis. It was important for us to give a snapshot of the current Muslim American community in the heartland and to really show people how beautifully diverse and interesting it is.

UPF—and the folks behind UPF—told stories about Islam and Muslims, and about America, well before many people understood just how important that would turn out to be. In short, you were way ahead of the curve. Now, of course, there are many more Muslim faces and ideas in these spaces—your co-host, Mona Haydar, is just such an example. Where do you think we should go next?

Here I need to qualify that I am a comrade to the Muslim American community. For political reasons, I prefer not to call myself an ally because that term tends to function on a one-way basis: allies don’t tend to be able to bring their own struggles to the table. Comrade implies a better form of mutuality in my opinion, a better ground for solidarity. With that said, my observations must be seen as those of an outsider, but also an insider if we can put it this way. As somebody who is deeply rooted in the Muslim community but is not a practicing Muslim, my observations here need to be understood from that perspective.

Several years ago, I developed a theory that Islamophobia is primarily an issue having to do with Americans perceptions of the Islamic faith and lack of literacy around the Islamic religion itself. I observed in my research that the civic identity of Muslims must be seen in distinction from how people come to understand the religious faith of Muslims. And I think what this means is that for those of us that do education on Islam and Muslims in the public more emphasis should be placed on educating people about the Islamic faith itself.

In the post-ISIS landscape, most Americans, if you look at polling on this from ISPU, you find that people view the religion of Islam as a totalitarian, anti-woman system of thinking. Education on Islam remains the biggest hurdle for Muslims living in the US. I am not exactly sure how one goes about promoting campaigns that do large scale education on the Islamic faith, but I think that must happen more.

The Great Muslim American Road Trip talks a lot about the marginalization of Muslims, past and present. There are fascinating insights into Black Islam, for example, as well as precolonial Islam, Muslim encounters with indigenous peoples, and the tremendous promise and potential of young Muslims today. But there’s not so much about tensions within Muslim communities—such as racism by and from Muslims, or misogyny by and from Muslims.

Maybe the Road Trip isn’t the right vehicle to tell those painful stories, but then that makes me wonder who should tell those stories—and how do you think we get people within Muslim communities to pay closer attention to the injustices at play in Muslim communities?

Perhaps some narratives that reveal the “dirty laundry” of the Muslim community can be tabled for the future when the wider public has a more sophisticated understanding of Muslims and Islam? Perhaps that should be a matter of “baby steps”? With that said, internal criticism of one’s own community is a sign of humility and maturity. We know the direction that internal critique can take and how people can abuse both the extent of the problem they are spotlighting and how those who do reveal the stories can be ostracized from the community.

We also know that Hollywood tends to secularize and omit religion from its narratives. It's not only Hollywood, but I would also say it is a general tendency of our culture. Just consider the 1960s—1970s era translations of Rumi into English by thinkers and writers like Coleman Barks. These translations specifically omitted reference to Islamic themes and motifs in Rumi and they went on to become some of the most widely purchased book on poetry in the United States.

In a way, the portrayal of more overt religious themes is a taboo that the culture industry enforces across the board broadly speaking. And because of this, it behooves Muslim storytellers to recognize those taboos and creatively work around them. Perhaps Muslim storytellers, unlike other devout religious followers, can be some of the first to integrate more explicit religious themes without facing the same cringe worthy response that many overt religious themes tend to receive. For example, overtly Christian films, and even often overtly Christian music is widely chastised and mocked by many. It all comes in varying shades of emphasis and tone.

What I'm trying to say here is that I believe that a more explicit religious theme should grapple with the human dimension. But I would also caution against narratives that essentialize Muslim culture as uniquely producing racism or bigotry. My first question would be: is that in fact something about Muslims and Islam that is producing that racism, or are there other social factors that need to be isolated?

I have to say this was a great watch—I learned a lot, I found myself really taken by the meetings and moments so powerfully portrayed. I'll recommend it to friends and especially families: There’s plenty to learn but also plenty to talk about. But what specific themes and ideas do you hope viewers focus on? Is there anything you hope they dig into more deeply?

I think one of the main themes, and certainly one of my favorite themes from this film, is the theme of what we might call the “hidden cultural influence of Muslims in America.” This hidden influence of Muslims stretches way back to the time of Christopher Columbus all the way up to the present. It should be seen as a source of pride for Muslims and a surprising revelation for everyone.

Tell us a little about how you got involved in UPF and where you, and UPF, want to go next.

I grew up working class, working as an assistant to a bricklayer, landscaper, doing odd jobs out in Oregon. I never dreamed of working with a group like Unity Productions Foundation, or even working closely with the Muslim community, or being involved in higher education as I am today.

I was drawn to this work with the Muslim community specifically because of the second Iraq War and a growing sense that I wanted to find a way to respond to this tragic event, to get on the inside of both protesting it and learning how we got to this point in our relationship with the Muslim world. Concurrent to that interest I was also a budding intellectual and had a strong interest in Marxism, socialist politics and was drawn to critical theory and philosophy.

So, what happened was that I became engaged in interfaith activist work and simultaneously went back to graduate school in philosophy. Over time I gained a professional leg up in the interfaith world before I met the founders of UPF. I felt called to do interfaith work, I re-connected with my Christian faith and worked with left-wing Evangelical groups. This was when George Bush II was in power, and the Evangelical-Muslim relation was quite tense and really felt at the center of geopolitics. I ended up being drawn to the work of the philosopher Slavoj Zizek who many young left-wing Evangelicals were into at the time, and I wrote my graduate degree on his ethics and politics. From there I got way into Lacanian thought and sought to combine my interest in Islam with contemporary Marxist theory.

All the while I had learned how to make films with UPF, and those skills were invaluable. The situation of modern academia does not afford someone from my background the chance to make a comfortable living so that chance was foreclosed to me. So, what I did was I forged a unique path that combined my calling: interfaith engagement with critical philosophy.

If a young person comes to you eager to learn more about what you do, what would you tell them? And what would you warn them about? (Because good advice isn’t just what to do, it’s also what not to do.)

My message would be to trust your calling and to never give up on what drives you and what really moves you. There are conditions that you must face in your professional life that may be perceived as obstacles, but my advice would be to continue to forge ahead. It is important to reach a place of excellence in what you create. sometimes it takes a very long time to arrive at that place. For example, I have learned a lot about making films and I have produced three or four of them. But I still have so much to learn. In my philosophy work and intellectual engagement, I have recently published a book on the family and psychoanalysis – this felt to me like I reached a level of excellence that I was not sure I could have reached had I not stuck with it and read like crazy. So, my message is simple: never give up and work hard.

If a young person comes to you eager to get involved in film, what do you recommend they watch?

Such a hard question! It would depend on what sort of film they are into. I really think that film can be quite stuffy and hard to relate to for young aspiring filmmakers. It’s important to demystify film and to show how low budget but high concept films can achieve a lot. I would recommend the early work of Brit Marling and Zal Batmanglij like Sound of My Voice and Another Earth to see how a low budget, but high concept film can really make an impact. Lately I have been obsessed with the work of John Cassavetes, the American avant-garde filmmaker who sought to capture the unique American madness of everyday life. His works like A Woman Under the Influence fascinate me.

Is there any movie or documentary—or really any creative project—you’ve seen recently that made you think, “I wish I was involved in that!”

When it comes to films, these days I prefer to be involved with the pre-production storytelling parts of the film process and less with the actual production process. However, I am trying to raise money to possibly make a major film on the Islamic philosopher Ibn Sina which would require filming along the old Silk Road and throughout the far east. If this happens it would be cool.

What’s one habit from your childhood that you’re glad you stuck to, that helped you in your life, that made you better at what you do today?

I was raised by a single mother and a stepfather who was an on and off presence in my life. This meant that I had to become a father figure to my little brothers at times and I think this also meant that I derived a sense of loyalty early on in my life. I have kept this sense of loyalty consistently in my life. And perhaps the importance of loyalty explains, at least in part, my work with the Muslim community over the years.

Does Islam Need Politics?

In case you missed it, a few weeks back I was on Wisdom of Crowds, a fabulous podcast co-hosted by Shadi Hamid and Damir Marusic. In this two-part conversation, these great co-hosts pushed me to go deep into some heavy questions, like whether Islam must include a political dimension, if it’s possible to be an atheist and a Muslim, whether America’s moved beyond Islamophobia, and why I distanced myself from Sufism, despite all the perspective I gained from Sufism.

The first part of this fantastic conversation is free; the second part is only for subscribers—and that’s pretty much the model of all their shows. I would tell you to subscribe, but that would sound self-interested; perhaps it’s more meaningful to tell you that I am a subscriber (it’s only a few bucks a month), that I love their podcast, and that it always forces you to think. (Not to mention they’ve got great chemistry, meaning that complex and urgent discussions are often fun and even funny.)

Of course, you can find this podcast—and incidentally The Rise and Fall of Mars Hill—anywhere you download podcasts, like Spotify or Apple.

As Many Caliphs as Muslims

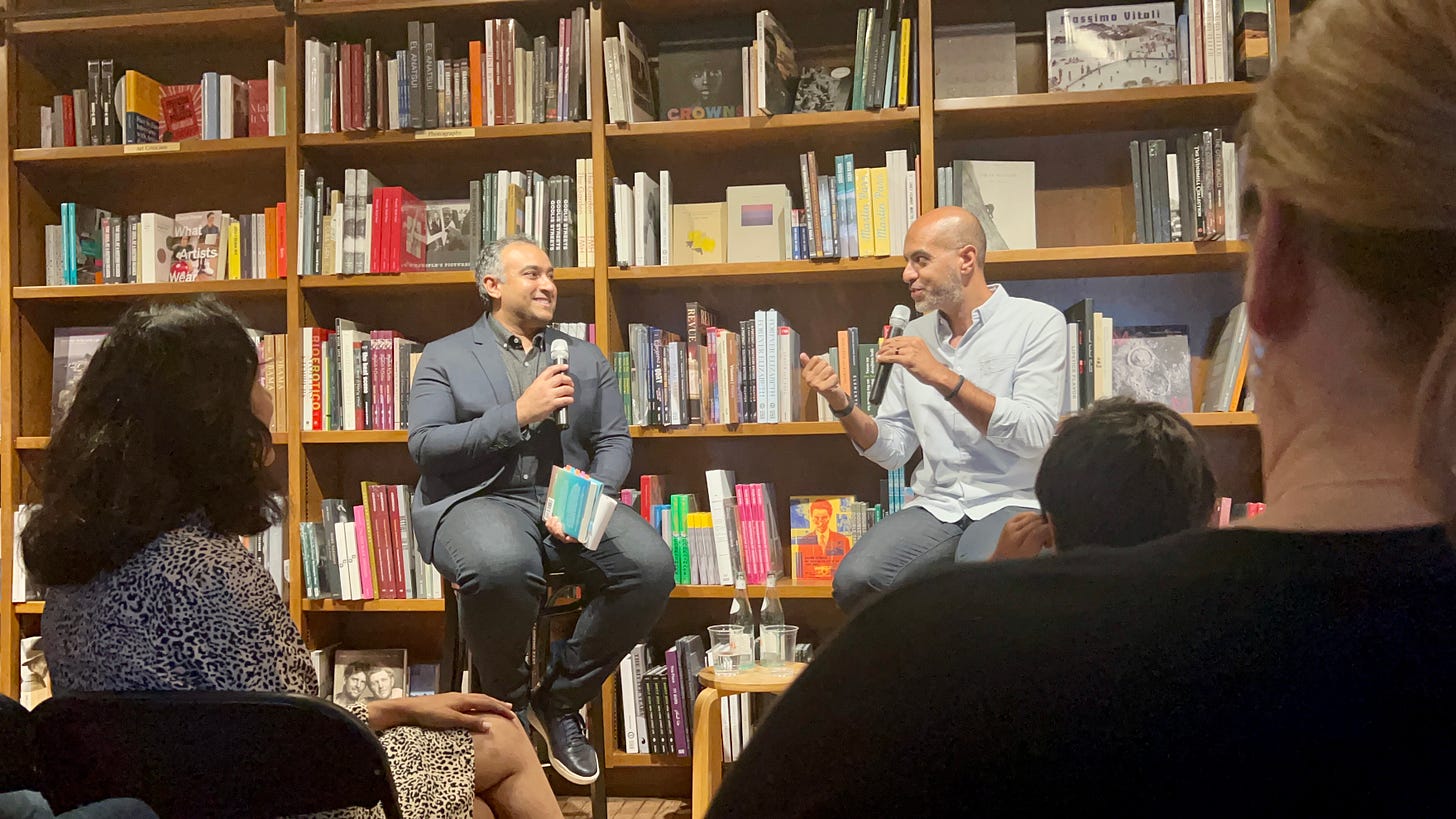

This past Wednesday, my good friend Imran Siddiqui interviewed me before a packed audience at South Florida’s fantastic Books and Books. It was a delightful engagement, with more questions than we had time to answer, and more than that, it was just really enjoyable to be in a thoughtful conversation with a smart and accomplished leader who could push me and my ideas—leaving readers with a better and broader perspective on the big ideas in Two Billion Caliphs.

But allow me to share this humble brag too: At the start of the event, Z volunteered to introduce me, something on the order of what she did in New Hampshire, but this was a longer introduction and, I have to say (excuse the pride and joy here, if you can), a different Z: She was even more confident, more poised, and more polished. In fact, she has a real voice—I mean presence, the kind of charismatic timbre that could mean hosting shows, giving talks, or simply captivating audiences otherwise.

Mashallah. May Allah give her the strength of character and the deep confidence needed to use this gift, cultivate this gift, and promote this gift in ways that make her and the world around her better.

Oh, and we had a great time in South Florida, too!

I’m so glad the kids get to see these engagements—that you can be proudly and unapologetically Muslim, but that a confident Islam doesn’t preclude (but instead demands) opening yourself up to others, taking critical questions, that it means laughing and joking as much as debating and proposing, that we can be ourselves, assert our beliefs, promote our perspectives, but hopefully always respectfully and with dignity. It’s not a lesson enough of us get.

It’s especially important too for young women, for the younger you are when you have these opportunities, the more confidently you can move through the world. It’s at the heart and soul of my book too, and my hope for these kids, and for all our kids: That we can be Muslims in the world, carrying ourselves with our heads held high, and that we can engage the world in beautiful, intelligent, and principled ways. They don’t have to be authors or public speakers. But they should be great at what they do.

And they should love to share what they do.

Shortly, I’ll share a clip from the conversation, where I discuss how the concept of Caliphate has been misunderstood, why it’s so vital, and what it could mean for the future of Islam—a future that is more local, nuanced, thoughtful, dignified, and free. A future that rejects despots and dictators, laughs at top-down enforcement, demands accountability, reveres transparency, and promotes moral agency, the right (and responsibility!) each and all of us has to live our faith to the best of our ability.

And so if you’re in Madison, Wisconsin, on Monday, July 11th, at 6pm—that’s central time!—then you’ll have a chance to be part of just that kind of conversation: my dear friend Kamal Marayati is interviewing me at A Room of One’s Own, an independent bookstore located at 2717 Atwood Avenue. Free, in-person, and open to the public: Come through! Copies of Two Billion Caliphs will be available for sale and signing. After that, the book tour kicks up again in the fall, inshallah.

Scheduled stops include Connecticut, Colorado, and Louisiana, with more in the works! If you’re interested in bringing Two Billion Caliphs to your community, congregation, or part of the country, just drop me a line. In the meantime, have a wonderful Friday, and a blessed Eid. May it be a chance to think deeply about what you love with those you love, to recognize the immensity of the sacrifices those who came before us made, and to be inspired to make sacrifices that will renew the world.

Salam!