I’ve been silent for too time. Some of that has been busyness, I promise. But a lot of that has been disappointment. That’s what this essay is about: When you imagine a certain outcome, experience the dissonance, and try to come to terms with it. Sure, I know, religiously, everything is written (maktūb), and most of everything is out of our control (qadr), but this is actually about religion—or at least the future of it.

Two years ago, I redesigned the high school halaqas with a huge and what I thought would be wonderful ambition in mind: We’d read a few books a year, vital texts that are lodestars for young Muslims, classics like The Autobiography of Malcolm X and far harder works, like ‘Allama Iqbal’s The Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam (okay, just a chapter, because it’s dense.) I wanted them to feel as I did, growing up.

I wanted to them to have what I only later realized in its fullness.

That I was part of a conversation that stretched across centuries and continents and, with enough hard work and diligence, I could be part of it, too. They could be, too. They had an obligation to, too. Yet that hardly came to pass in our halaqas. In immediate consequence of the October 7th attacks and the war on Gaza, with a genocide unfolding, we could hardly not talk about that in depth.

But there were bigger challenges, systemic impediments really, and these are, in no particular order, the kids’ fault, the adults’ fault, and nobody’s fault. Because, they were, on the whole, not very interested in reading at length. Having never developed the muscle of reading, having never stretched their attention to failure, they were winded within minutes. I know some of my students read the book. But I also know a lot of them didn’t. And what do you do with that?

You certainly don’t have the halaqa you expected.

Conference of the Nerds

I’d expected that I’d have at least a few students who wanted to dive in deep, who were mentally, emotionally, and intellectually ready for rigorous conversations, who could be pushed and who wanted to be pushed, who were interested in growing academically. Before you say I’m asking for too much, consider that I’m really not. Plenty of kids play sports and are happy for coaches to push them, even challenge them. Some of them calmly put up with coaches who yell at them for minor mistakes (to be clear, I wasn’t going to yell at anyone for mispronouncing a word, but it’s strange, to say the least, that it’s acceptable to yell at a kid for missing a pass… but we [rightly] wouldn’t accept a parallel response in a literary context.)

When I was growing up, there were lots of kids—like me—who wanted tough teachers, who wanted to achieve academically, who wanted to read broadly and deeply, who loved math and science, who were nerds and proud of it. Didn’t I have equivalent students? Part of the problem, though, was that I don’t grade. I can’t grade. I don’t think that’s what we want out of halaqas (though, fairly, why not?) and the students were there for vastly different reasons, which meant the students I did have, who were really interested in the material, couldn’t get the time, attention or consideration they’d deserve, but this was a problem without an apparent solution.

If you’re wondering why I’m concerned, you could start with this great essay by the New York Times’ David Brooks, “The Character-Building Toolkit,” in which he writes:

I’m one of those people who think character is destiny and that moral formation is at the center of any healthy society. But if you’re a teacher in front of a classroom, with 25 or more distracted students in front of you, how exactly can you pull this off?

It’s a brilliant piece and you have to read all of it, preferably a few times. Later in the piece, Brooks outlines how learning can produce character (for a Muslim audience, studying adab produces adab):

Deep reading. Students learn about these traditions by studying the great texts of each. It’s noteworthy that most great moral traditions ask people to passionately study difficult texts — whether it’s the Torah, “The Odyssey,” the Quran or even “Das Kapital.” The charge is not just to read certain books, but to devour them, to enter into them and struggle within them, until the deeper meanings enter the blood. Kafka famously said that “a book must be the ax for the frozen sea inside us.”

You don’t experience that if you’re just skimming a book enough to get through class. One of the great morally formative institutions of my life was the University of Chicago. From the vantage point of my 19-year-old self, my professors’ learning and wisdom was beyond immense. They burned with an enthusiasm that if we would only read the great books passionately and think about them deeply, we would know how to live. This is an infection I have never gotten over.

Got that?

Except too often, these days, we avoid reading, except when we absolutely have to.

There are good alternatives to reading, in terms of building attention, focus, mindfulness, an appreciation of beauty, the world and expertise—playing an instrument or a sport. But, still, reading matters. The Qur’an came down as a scripture for a reason. For generations, people repeatedly revisited texts; going back to my theory that in order to thrive, we can’t forget what we once had to do to survive, I wonder: Is it possible we don’t yet realize the full value of immersion in a text or a tradition, going back to the same sources of meaning, again and again and again? Not only do we not read, though, we hardly focus on anything for more than a few minutes.

What kind of faith, and what kind of faith community, and more broadly what kind of society, would result? A case in point: When Donald Trump proposes buying Greenland, many of us are shocked. One might point out, however, that we bought Alaska back in 1867, a purchase engineered by William H. Seward, who served under President Lincoln—a very good President, on almost any measure, and a remarkable person, on almost any measure. Seward, in turn, opposed slavery and believed it was the destiny of the United States to rule over the entirety of North America; he saw the purchase of Alaska as a move in that direction.

A policy we might feel flabbergasted by is, actually, much more than a century old. Before World War II, and certainly World War I, plenty of elite white Americans were skeptical of if not hostile to Europe (we fought wars with Britain, twice, and Spain, once) even as they believed in expanding the American empire within the Western Hemisphere: Monroe Doctrine, Manifest Destiny, a lot of this has happened before. That doesn’t mean you have to agree or approve. But we should know that the world didn’t begin with us — because without that, we won’t remember that the world doesn’t end with us, either, and we can’t see what’s clearly coming our way.

I Never Had A Sega

The following sentence is not true: I’ve read some great books lately. At Cincy’s Mercantile Library, I was recommended Harrison Scott Key’s How to Stay Married (that’s a book that knocked me over a dozen times). I’m captivated by Jonathan Eig’s biography of Martin Luther King, Jr. I’m also in the middle of reading Steve Coll’s The Achilles Trap, about that other Baathist tyrant, Saddam Hussein, the supposed WMDs, and an unnecessary, devastating American invasion. Except that I’m not reading them. I’m listening to them. I hardly have the time to sit and read.

To be clear, I do read. But not as much as I used to or even as much as I would like to. Part of that is because I hardly have the time. Who does? (I’ll get back to that.) Part of that is that my phone has shattered my ability to be at peace with calm and quiet. A recent Substack I read, Regina Doman’s The Culture Recovery Journals, compared smartphones to Tolkien’s Ring of Power; no matter what we do, it ends up in our pocket. I’ve become much more conscious of this, and when I find myself caught in my phone, I make it a point to put it down.

But this starts with (at least most of us) admitting that we’re addicted. We can’t be without devices and distraction. We’re so easily bored. Even when I’m reading, I find myself looking for my phone, even when I don’t want it or need it. If both of these things are true — time and dependency — for me, then aren’t they for our kids?

Our youngest spends about a total twelve hours a week on after school music and sports, not to mention time going and coming, not to mention four hours a week between Qur’an and halaqas, not to mention busier weeks. (At least one adult is therefore also similarly committed.) This isn’t a bad thing per se. But I do read it against something that worries me: When I was growing up, neither society nor parents nor kids themselves had such outsize expectations for constant engagement, ranging from the fear of missing out to college admissions.

Mostly, our parents — who were good parents, mind you — left us alone, which gave us time to dive deep into whatever we liked, undisturbed. I spent a lot of time reading Islamic history, yeah. I loved cars, too. Languages. Tolkien. Sci-fi. Star Trek. Basketball and the Lakers. Dune. Tennis, watching and playing. I spent a lot of time reading everything I could. Writing, too. I loved my Nintendo 64. (GoldenEye might’ve been the peak of Western civilization and I’ll die on that hill, try me.) As soon as I could drive, snowboarding. Also driving. Cars. Who amongst us does not want to have a Porsche 928? Weightlifting, eventually. Poetry. Philosophy. Swimming.

Most of these things, I did on my own. Did we lose something along the way when we turned everything into an organized activity with metrics and, God help us, apps? (Speaking of cars, my primary aversion to EVs is their utter unimaginativeness and undeniable hollowness—their interiors not only feel insubstantial and rootless, but make me feel like I’ve gone from having a phone in my pocket to sitting inside a phone, designed by someone who doesn’t seem to think humans are organic beings with history, spirituality, and emotion. Do I really want my car to be a screen?)

Have our kids lost the time and space to just explore, without the need to master, prove worthy, win competitions, or augment resumes? What happened to exploring for the sake of exploring? Then we throw smartphones in the mix, plus a low-trust society, the absurd nature of suburbs that make it hard to get around without a car, a prevailing belief that kids should not be out on their own. Often times I hear younger kids say things like “it’s not my fault, so it’s not my responsibility.” This might be the best mark of adulthood I’ve heard: Even when it isn’t your fault, it is your responsibility. A lot of the world we live in is the result of forces we can’t control.

Yet we still have to do something about it.

In decades to come, we’ll have to do a lot of rebuilding. Our way of life isn’t sustainable. (The tragedy in California underscores that—Trump will sadly likely make it worse.) We will have to rebuild. We have to create more resilient homes, literally, but also culturally. While we’re on the subject of rethinking college, and how the Ivy League ruined America (see also Malcolm Gladwell’s latest, on admissions, race, and privilege), we should also collectively reconsider how we raise kids. But in the meantime, we must also do what we can. For my part, that means sharing the halaqa from this fall.

Now that we’ve finished a semester, I can.

I took Brooks’ challenges. Maybe I can’t grade these kids. Maybe I only see them once a week. Maybe they’re not going to read outside of class. So I’ll do the next best thing, even if it might feel to them at first like their teacher has gone crazy: We’re going to keep talking about the same thing, over and over and over again. We’re going to approach the same question from so many different angles that it’ll be like we’re reading the same text, over and over and over again. Will it work? Time will tell. Do you think it’ll work? Subscribe and stay tuned.

But let it never be said that we faced all the currents of the world and gave up. That’s part of the value of an education that emphasizes rigor, autonomy, and creativity. I was blessed with that—and that’s why I keep searching for ways to reach people, inspire people and empower people. Something must be working, because the high school girls’ halaqa is now at 13 students, and we’re just returning the same thing, over and over and over again, from different angles and perspectives, revealing the richness, density, complexity and beauty of history. They get loud, they debate, they disagree; last week, for example, we talked about the Caliphate of Abu Bakr, may God be pleased with him, DEI programs, affirmative action, the Electoral College, and Sunni Islam, and what these have to do with each other.

I should probably write a book about this. Or at least a Substack.

Around the World (and the Web)

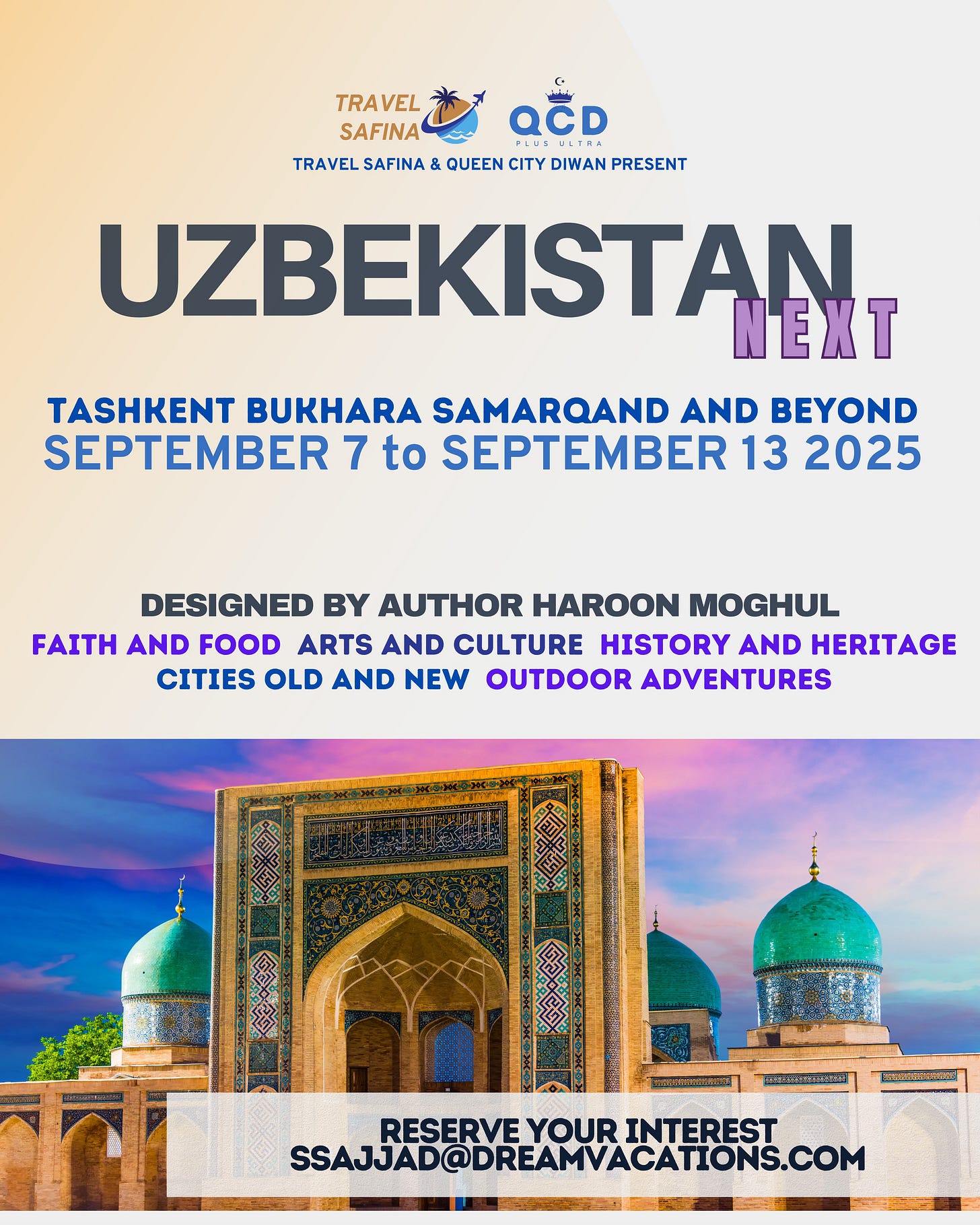

Last year I started a travel company, Queen City Diwan. We build unique travel experiences that bring Muslim history to life. I’ve poured over three decades of reading, writing, teaching, building, scaling and mentoring and traveling, and the result of our first trip—last November in Spain—confirms that it really is possible: We can have fun, take friends and make friends, make memories, and come back not just inspired but empowered. Which is why we’re at it again.

In collaboration with Travel Safina, we have three experiences coming up (and many more planned!) The first two trips are for travelers of all ages and life stages. From September 7 - 13, 2025, we’re touring Uzbekistan. From November 2 - 8, 2025, we’re touring Muslim Spain. Both of these trips are designed to explore faith and history, yes, along with arts and culture, food, music, literature, made to take friends, designed to help us connect to each other, and provide life-changing, big-picture perspective all along the way. I travel with the group from start to finish, offering classes, insights and context that make history relatable, accessible and inspiring.

The third trip is a little different: It’s for a select group of college students only.

Queen City University is a retreat designed specifically for young Muslims, aged 18-22. In a warm, welcoming environment, they’ll travel across the south of Spain, learn about history, and benefit from life-changing classes, vital professional and personal mentoring, deep conversations about the past, present and future of Islam, while also meeting dynamic Muslims doing great things in their careers and communities. Because the reality is, our communities don’t yet give our kids the resources they need to realize their potential.

I’m building this trip, too, will be leading the trip, teaching parts of it and designing the curriculum. I’ll also be joined by two accomplished young Muslims who will serve as mentors and chaperones, for a really exciting and engaging experience.

This college retreat, Queen City University, will take place January 3 - 9, 2026.

If any of these are of interest, you can leave a comment below or message me directly (space is limited for all these trips and tours—part of what makes them special is the intimacy and scale of a tight-knit community).

But there’s far better news still! My beautiful, brilliant wife is now on Substack, with a Substack that will soon rightly eclipse mine—Thin Places. It’s fantastic. I could describe it, but I wouldn’t do half as good a job as she does.

Thank you for reading.

But I’m not going to let you go without homework: Find a text you love. A poem, a prayer, a short story, a novel. Dare to read it twice.

Salaam Haroon, you made a lot of very deep and interesting points. I think you hit the nail on the head about the smartphones’ ubiquity and their vice grip on our attention spans. Introducing reading to younger audiences who are increasingly making use of AI, plugging and chugging summaries of texts online and just in general using shortcuts instead of developing their ability to concentrate and read is definitely an uphill battle. Maybe you could talk about smartphone usage and attention span. It seems you’ve also experienced life before smartphones. High school students today haven’t. They think it’s normal to be constantly on their phones, and even many of us older folks are too. You said it yourself, you’re listening to books rather than reading. Honestly, we hardly have the mental freedom to just think and just be. We’re constantly inundated by media — all of which is trying to grab our attention.

And regarding your point about your childhood, don’t forget that people today are increasingly always online. Young people especially are living curated lives, where they share intensely personal details about their lives to their peers. If something isn’t cool or accepted, it’s risky to engage in it. And if it’s not shareable…

Just some food for thought. Looking forward to reading more of your work.

Hi Haroon. i enjoy all your substacks, but especially this one. i teach grad students at a major university and i too see this distraction among students. it's hard to get them to read a book. many of them won't even read news -- and they want to be journalists and writers! And, as you note, the problem extends to us. we have so many distractions. it is hard to sit down to a book or a newspaper without being pulled away by the next shiny thing. i appreciate your efforts to stay focused. i may be one of your few Jewish readers, but i have found the sabbath to be a great escape. i do not use my computer or my cellphone. it is a day i actually read books. i'll pick up the New Yorker and read it cover-to-cover. i don't know if there is any equivalent in Islam. But escaping the digital madness is something we should also try to build into our lives.