Last month, a local dad reached out. Because I’ve been teaching high schoolers, he reasoned I could reach his son, a college student facing a man’s biggest decision—choosing the woman he’ll build the rest of his life with. That’s how this young man and I ended up across a table at First Watch. He looked nervous, probably because he’d never met me before. I immediately sought to allay his concerns.

I told him that he didn’t have to heed me. But I hoped he’d hear me. That he’d be open to sitting with what I had to say, and reflect on it, and that God willing this would help him in the weeks and months to come. A young man at the start of the rest of his life has a right to hear from older men who care, who’ve been there, who maybe (as in my case) had to learn some of these lessons the hard way.

And yes, I told him in no uncertain terms that this was the most important decision he’d likely ever make. That if his father was worried, he had every right to be; maybe his father hadn’t couched his fears in the wisest or clearest way, but that didn’t make his underlying concerns illegitimate. This young man opened up pretty quickly, confirming that he was in a serious relationship.

That they were looking to marry. Wasn’t that a good thing, he asked? Of course it was, I told him. I wished him every happiness. But my obligation to him included helping him think about perspectives maybe he hadn’t thought about, so that whatever choice he and his fiancee made, their future ahead might be better for it. And that choice, I insisted, was ultimately between him, her and God.

Popping the Question

Marriage is a strong sunnah for very good reasons. The older you get, the more you realize just how important those reasons are.

If you’re ready, I told him, you should get married. I’m not one of those who weirdly propose delaying years, in the ultimately self-defeating way my parents’ generation did, on the assumption that waiting until you’re thirty, and practically near the end of your biological clock (men and women alike) is wiser, smarter, and makes marriage more likely to succeed. If you’re ready, move forward.

But are you ready? As we talked, and he shared more about her, their relationship, and their hopes for the future, I told him it sounded like he hadn’t sat with some important, even vital questions. Because the most enduring choice we make isn’t where we go to college, what career we pursue, or even where we live.

It’s who we choose to spend our lives with.

For men, who we marry will determine so much of the rest of our lives—far more than most young men realize: Where we live, what kind of career we pursue, how and who we socialize with, whether we are ambitious or apathetic, whether we’re eager to come home or alienated from what should be our refuge—not to mention how we raise our kids. As far as I can tell, no other decision comes close.

That doesn’t mean college doesn’t matter or where you live doesn’t count. But actually, those impact who’ll consider marrying you as much as who you’ll consider marrying. Everything is connected. My job wasn’t to tell him who to marry, when to marry, or any of that. It was to encourage him to ask the right kinds of questions, beginning with this: Is she the right person for who I am — and who I must be?

And the one that we spend even less time with: Am I the right person for who she is — and who she’s been raised to be and probably will become?

The Signal and the Noise

A lot of people get married because their heart inclines to a person. That’s great, and that’s wonderful, but that’s not enough. You have to want to be together, of course! We get that message from popular culture, though, which makes life a lot easier. What we hear less of and should hear a lot more of: You have to have enough in common that you’ll be able to keep going when the going gets rough. It always does: Life isn’t easy.

I told him: “You gotta make this decision for the right reasons—for you personally, and her, and for your futures, including your kids.”

Because, I told him, your kids, who don’t even exist yet, already have rights over you. You should ask if she’ll be the mom your kids deserve. She should, with equal weight, ask if you’ll be the dad her kids deserve.

If you want to know whether this marriage makes sense, make sure I’m not the only person you talk to, too. Ask good people for their advice, I told him, people who know you well. To be clear, that includes dear friends. If you have that kind of relationship with your siblings, awesome. That must also include people older than you and happily married, though, because we learn from people who’ve lived the life we seek.

That should also include your parents, since most parents do actually care a lot and do actually know you extremely well. Sometimes we parents don’t know how to express our concern, our knowledge, our affection. Sometimes we express our love in entirely convoluted, even self-defeating ways, but it’s still love. I do that a lot, actually. I recognize this in myself even more because it happened to me, when I was a kid.

But looking back now, I appreciate my parents’ counsel on so many things, although they often didn’t know how to communicate their counsel in a way that made sense to me. My dad, more than my mom, encouraged me to be a doctor, though never stringently. He’d just tell me how much money I could make as a doctor (he didn’t understand what I wanted to do, which was part of his stress).

While of course I didn’t become a doctor, I’ve come to see that what really animated him was the hope that I’d be independent, able to live the life I deserved. As far as he know, medicine and mostly only medicine offered that kind of material security. Salary was a proxy for a parent’s fear for his son. I told this young man this story and then told him he must hear through the noise and find the signal in the sternness.

You might reflexively dismiss everything your parents say, I admitted, but there’s probably more there than you realize. A lot of it might feel wrong. Some of it might be wrong. But more of it may be right than you realize, and on what basis are you determining that, when you don’t even have half the life experience they do? If you can’t hear them, then take the time to talk to someone who’s been married for a while.

Someone who can push you to think beyond your experience.

Better yet, someone who can make sense of their advice.

Opposites don’t attract—they combust

There’s plenty of silliness out there just like this—because no, opposites do not attract. Here’s some better advice for how to pick your lifelong partner.

Yes, you want a woman who you love, care for, and are attracted to. Who loves, cares for and is attracted to you. That part should be self-evident.

In his case, that part was taken care of. But that’s hardly everything.

You need someone who’s similar enough to yourself that you have shared priorities, ambitions and, most importantly of all, frameworks. Your families have to be able to get along (more on this later). That doesn’t mean people from different backgrounds can’t get married, though they should understand the work they need to do. Because when bad things happen, and they will, you must be able to face them together.

Once you’ve established that you have common priorities, ambitions, and frameworks, then and only then should you determine whether you’re mutually reinforcing. Not opposites, but complements. Some of that is who you are. A lot of that is your willingness to bend and adapt (another reason why waiting too long to look for a life partner is tough: We become less capable of growing together.)

What does it mean to complement each other? Ask some questions! Do you and her work better together—or better apart? That’s not about different values, but different strengths. If both of you have very specific careers, that require you to live in different cities, well, that’s not going to work—unless you can find some way to adjust your expectations (and if you can’t do that mutually, I’m not sensing much love.)

I told him he should also be ready to complement his future wife not just as a person in the abstract, but in the practical realities of life.

For example: There’s many weeks where, because I’m working from home and my wife isn’t, I’m on laundry duty. I’m never allowed to cook, however, as nobody wants to eat my food, beginning with me. Because I’m good with other responsibilities, however, like vacuuming, this is never held against me; also, again, I cannot stress this enough, nobody wants to eat my food.

On 1st Ramadan, Haroon will have charge of two of the kids. He’s excited to share his ideas for suhoor (sehri), above.

But a man and woman in love should make sure they have the same beliefs—about what’s important, what’s urgent, what’s right and what’s wrong, what they can accept and what they can’t. Enough that they can work together, and complement each other… instead of working against each other, and undermining each other, because one day very likely, kids will enter the picture, and then most of the things you thought were important or even possible will go flying out the window.

You’ll be in an entirely different reality, where everything you do is for them, not just financially or educationally or emotionally, but spiritually and religiously, and how do you do that if you aren’t on the same page, let alone reading from the same scripture? What generally happens when parents aren’t on the same page is one of a few difficult outcomes: One parent must yield, building resentment. All the same, kids feel torn: Choosing a faith means choosing a parent.

Both parents dial down their moral commitments in other instances, which sometimes creates distance from extended families, which deprives us of support networks… These aren’t automatic outcomes, and mature couples can escape these trajectories, but it’s not easy—and, in my experience, it’s actually quite hard on both partners. That hardly means we simply look for people who look like us: I’m talking about real maturity, real compatibility, and serious commitment.

There’s an easier, if also harder, way to think about this.

Imagine You’re Not

It’s unpopular these days to acknowledge that we are not islands. The nuclear family is a dangerous myth—few families have the resources to survive as a coherent, isolated unit. And if you’re trying to raise Muslim kids, you’ll still need extended family, community, and multiple mentors and sources of meaning and advice for your children. I mean, just consider the situation I was in over breakfast.

A dad we know had asked me to talk to his son, who was on the verge of marriage; the dad believed I had good counsel and he expected (and I agreed) that this conversation was part of my obligation to him, to our community, to his son, and to our faith. That kind of solidarity and fraternity doesn’t just pop up out of nowhere. It takes years to build (and sustain). Sometimes we will be resources for others.

But there are times when we need people to be resources for us.

You need that community.

In the case of this young man, as you can probably guess, the reason his father was so concerned was because his son was in a serious relationship with a woman who was not Muslim (and who was, to be clear, not interested in becoming Muslim, either.) His father thought his son was underestimating how significant this difference was. The son in turn believed his father was exaggerating how big of a deal this was.

But I told him that this difference in faith actually mattered more than he realized and would grow to become more daunting. Because it’ll take a lot of patience, resilience, and honesty to navigate their lives going forward, especially once they have kids. I’m not saying that’s impossible. But I am saying that many people find these marriages far more difficult than they initially imagined.

What happens with aging parents? How do you pick a community to belong to? And most critically of all, what about your kids?

You may not think certain differences matter, I explained, but I promise you that your ability to prosper, to live a good life, and to raise strong kids depends on being part of strong families and strong communities. Your kids’ ability to define themselves, establish priorities, and structure their lives ethically requires a coherent belief system, a feeling of belonging, and a deep moral framework.

You and your wife have to provide that—together.

Your spouse should see eye-to-eye with you on life’s most fundamental questions of life. Of course, if religion isn’t much more than an identity marker to the Muslim partner, then this is not a big deal. But if you think you can be devoutly Muslim, your wife can be agnostic, and this won’t affect your marriage, or your kids, or your future together, then I think you’re not being honest with yourselves or each other.

I told him I was going to share a scenario that makes some people uncomfortable. “And if it makes you uncomfortable,” I told him, “that’s something to think about really honestly and seriously.”

A year ago, I found myself in a similar kind of conversation in Denver, with a young man who was very excited to get married—to a woman who was not Muslim. Her parents were hesitant while his parents were adamantly opposed. Unfortunately, as I inquired further, it seemed he himself hadn’t thought through what the marriage would mean, require, and could result in for him… and for her.

When he told me that he wanted his kids to be Muslim, I was confused: What kind of pressure would that place on his wife, who wasn’t interested in converting? And wouldn’t that mean cutting her out of a major part of her life with kids who would probably be much closer to her than to him because, you know, she’s their mom? (And rightly so: “Your mother, your mother, your mother,” the Prophet [s] said.)

And how would they navigate that? “She agreed I can raise the kids Muslim,” he said.

“Okay but don’t you want to raise the kids together?”

He paused, the question never having struck him before. Not to mention: What world are you living in where you’re going to have that much time and who is your wife in the meantime, just someone who’s in the house and hanging out? A marriage is a partnership, I said, and it isn’t fair to you or to her to be pushed to compromise on something that was so fundamental to each of you.

It was one thing if they were both in the same place, with neither of them particularly invested in a specific religious outcome, but here… well, I could see all kinds of problems, now and in the future.

Which is when I told that Coloradan: Marry someone who you’d trust to raise your kids if something happened to you.

If you don’t think they’re able to be the role model you want your kids to have, the parent you believe they need, that’s not the right partner for you (and you’re not the right partner for her!—she deserves to have someone who respects her beliefs, contributions and perspectives and invites them as opposed to limits them.)

You might love each other. But you’re going to force her to compromise, or yourself to compromise, in ways that might become extremely hard.

To make it work, because who doesn’t want to make it work, you might withdraw from communities and religious institutions more broadly, which makes your immediate family life easier, but also deprives your kids of religious resources, institutions and models they will need and you will one day wish you had.

Which is where and how we ended the conversation at First Watch.

Marry someone who helps you become the kind of person you believe you should be—who you believe your kids deserve, who you’d like to be at the end of your life, who can support you. You should empower each other, not constrain each other.

I asked him if the woman he wanted to marry was the person he wanted his kids to grow up and be like. Before he could say anything, I asked him if he was the kind of person he’d want his kids to be like.

Before you worry about finding the right partner, you’ve got to be a potential partner—and that starts with asking the right questions (and pursuing the right answers.)

Around the World on St. Valentine’s Day

If you haven’t subscribed to my wife’s wonderful new Substack, Thin Places, you’re missing out: In her latest, she beautifully explores how space can encourages us to connect to our history, to the world around us, and to the deepest and calmest parts of ourselves.

As she so powerfully puts it,

“Yet in an era of instant hot takes, spaces of learning have always signified something more profound to me. They represent not just learning but the possibility of transformation, not just knowledge but the promise of discovery. Their architecture is woven into my aesthetic DNA, speaking to something deeper than mere nostalgia—a belief in the power of spaces that invite us to think beyond our immediate circumstances, to reach toward understanding that transcends our current moment.”

While I’m especially honored she featured my great-great-grandfather’s books (he was a scholar of religion; we have a passion for studying and teaching faith in our family), I found her evocations of universities, libraries, schools, masjids and churches as places where we find transcendence and connection especially necessary now even as they resonate with who I am and what I’ve lived through.

Part of the reason I’m building tours and creating excursions is because I want to share the depth and beauty I’ve seen (and the impacts these had, making me into who I am today.)

While a lot of people have responded to the Trump administration’s mad dash through (and against) the collective wisdom of our democracy with panic, I think we should all heed Ben Rhodes right now, because the old America is not coming back:

Those of us alarmed must recognize that there will be no return to the past — no alternate story for how to make America great again or restore a lost post-World War II order. There will have to be new ideas for how the United States can constructively engage people around the world and peacefully coexist with other nations. To reach that future, however, we must look inward. It’s not enough to defend the idea of foreign assistance or oppose territorial aggression; we must also become the kind of nation that is able to see our own self-interest as connected to something larger than the whims of strongmen.

Instead of rushing to meet Trump’s freneticism with an equally thoughtless and aimless madness, we must slow down and reflect on what it means to rebuild—and that begins with connecting with our values. If a policy feels wrong, it’s probably wrong. When a policy is egregiously wrong, like gutting foreign aid, rampaging through the government that keeps us together, or proposing ethnic cleansing for the sake of real estate deals, let’s make that not the end but the start: More than identifying what is wrong, that identification should mean simultaneously underscoring what we stand for. A value is made visible in its violation.

On the basis of those values, and only with those values known, can we build an alternative. That’s why I’ve spent the last few weeks of the halaqas talking about how we translate our deepest principles into the world we live in now.

I’ve taken to talking about DEI (diversity, equity and inclusion) in recent weeks not because I specifically defend DEI as it exists, but because I think we are facing people who believe that pure egoism, narcissism and aggression will secure America’s future. This is a dangerous delusion, of course; there’s all kinds of reasons why this is true, which anyone who spends time studying history, actually believes in scripture or who has been truly and meaningfully married would know.

We are strong in proportion to our ability to prepare those who come after us for our absence. I will soon assign my students this beautiful News Lines essay on Iraq and Syria by Kamal Chomani. When we include, and establish a government that reflects all its peoples, we are less likely to collapse into chaos or paralysis. Our Founding Fathers knew that—that’s why we have an Electoral College. That’s why Washington stepped down after his second term. That’s why Lincoln built a team of rivals.

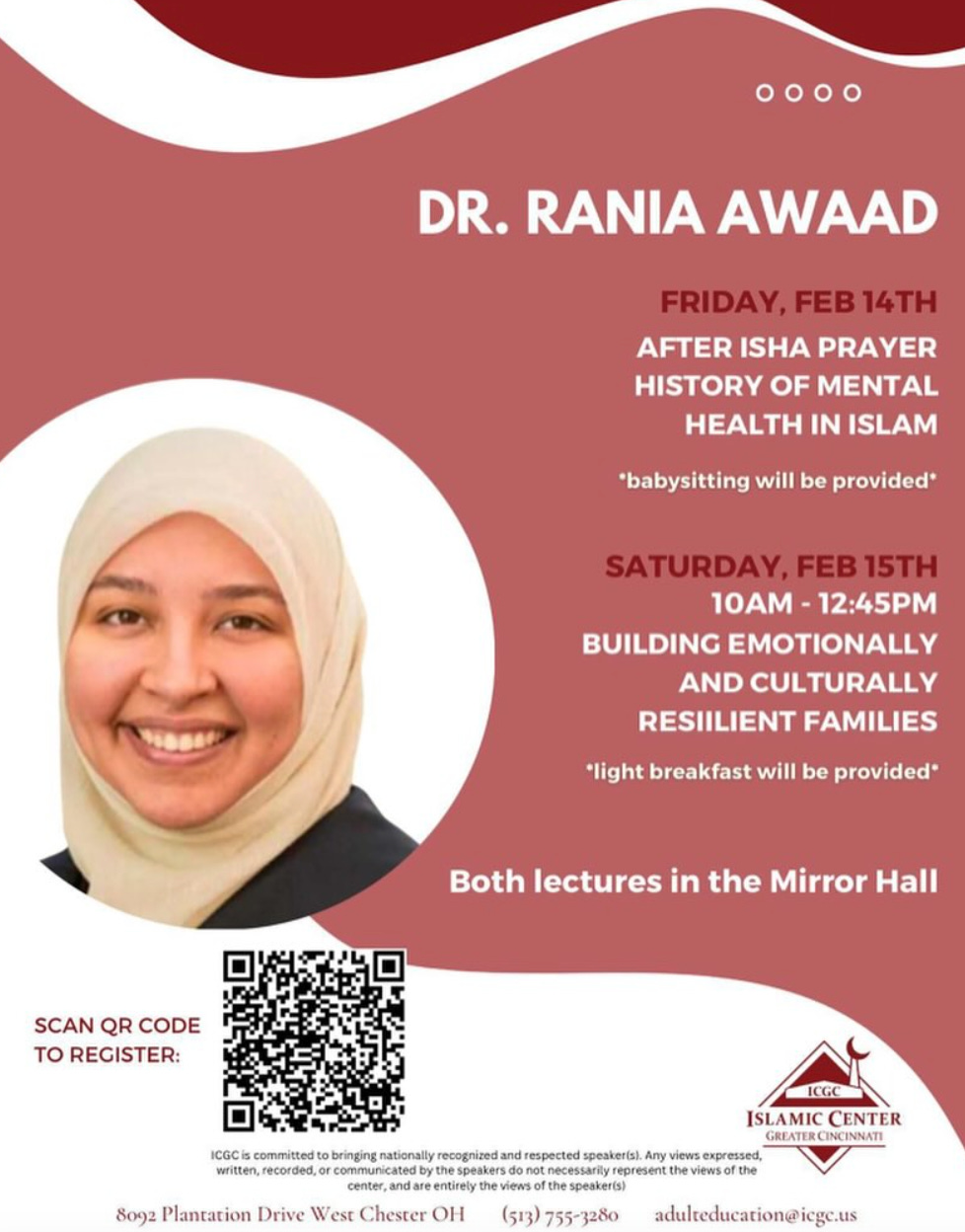

If you’re in the Cincinnati area, Stanford’s Dr. Rania Awaad will be at the Islamic Center of Greater Cincinnati on Friday evening and Saturday for a vital pair of lectures: “The History of Mental Health in Islam” and “Building Emotionally and Culturally Resilient Families.” Registration is required.

For those who don’t know, Dr. Awaad, M.D. is a Clinical Professor of Psychiatry at the Stanford University School of Medicine where she is the Director of the Stanford Muslim Mental Health & Islamic Psychology Lab as well Stanford University's Affiliate Chaplain. She also serves as the Associate Division Chief for Public Mental Health and Population Sciences as well as the Section Co-Chief of Diversity and Cultural Mental Health.

I’m looking forward—I need to hear her perspective.

Yeah, these last few days have been hard ones. I’ve been reading up on Uzbekistan and Andalus in preparation for Queen City Diwan’s upcoming September and November tours. In Uzbekistan and Andalus, devastating defeats by rivals led to the sacking, burning and looting of great cities, which meant, among other things, libraries burned and generations of knowledge lost.

Those were tragedies, of course, but they read differently right now: Here in our own country, I’m watching a President and his team effectively sack our own culture, heritage and achievements, including our image in the world, our knowledge and our integrity. This will not be easy to recover from, but we can. Against all odds, many societies endured (with great hardship) and did not lose themselves.

That is possible, based on who we are and what we stand for—and stand against. In designing these tours, I make sure we talk about what happened, of course, but also what we can learn (and how we can incorporate that knowledge into our lives.) If you’re interested, you can learn more about these unique experiences here.

Lastly, congrats to all my Philly friends and fans. That was not the Super Bowl we expected, but maybe it was the Super Bowl we needed.

A single man at halftime showed more courage and decency than practically our entire political class combined. There are many more courageous people in America, God willing. We must come together around our shared hopes, with focus and fortitude. I believe we know what we are resolutely opposed to. I hope we know what we’re for. We have to figure out what it means to walk that path.

We can only do that together.

Amazing article haroon!! One for my kids to read when they’re old enough.

Funny story, when I was on umrah I met a dad and his wife who was telling my in-laws and me the story of how he proposed when he was 16 years old (in high school) to a Muslim girl (also 16 years old), and how he just knew he was going to marry her from when he was 5. They grew up in the same community. We marveled at the gall it takes to be that confident as a young man and to convince the girls dad (Pakistani dad) “yea I can be a man” at 16.

I asked him, would you take that kind of risk for your daughter?

He said, yes, but I need to know him from the community.

The frameworks is not something people think about enough.

Parents use profession as a proxy for character but that is really flawed. But I’ve seen therapist do the same thing.

Lawyer = ocd tendencies

Writer/artist = unstable and poor with money

But how you are raised and how you want to raise your kids will make a lot of things easy or difficult.

I think I share the story of a young couple married in high school because it goes against my own preconceived ideas.

Very intriguing post. I admire how you conversed with him and gave him councel, in a way where you were simply trying to equip him with questions and insights for him to work with, rather than telling him things that would go in and out his ears.