For Some People, That's Where Their Islam Goes to Die

The story of an early Eid gift ... plus actual Eid gifts

Normally I pause the halaqas during Ramadan—the students are tired, the parents are tired, I am tired, but I like to tell myself I’m teaching by not teaching.

Growing up, I found Islam as identity inescapable—I’m a visible minority with an obviously distinct name. For some people, though, identity is not just where their Islam starts, it’s where their Islam goes to die. A marker of who they are or, more accurately, who their parents were. How they were born. Not how they live and certainly not how they will leave this world.

Like Jay Shetty wrote in Think Like A Monk, many people never graduate beyond seeing themselves as they believe other people see them. When they are tested, or have substantive life choices to make, religion hardly ever comes into the picture.

Of course, Islam is made to be more than that.

But many of us only move to the next obvious level: Islam as community, a kind of collective identity, which of course is part of our faith (ummah abstractly, taraweeh literally, searching for parking so you can get to taraweeh). Except that’s not the ultimate point either, is it? “I have not created jinn and humans except to worship Me,” God says in the Qur’an.

In the worst instances, this becomes a politicized identity, a kind of ethnocentrism or blind nationalism, my-ummah-right-or-wrong.

Even in positive instances, though, this is not our purpose in the world.

Sometimes we become so caught up in the hustle and bustle of Ramadan, the inescapable and wonderful energy of the month, the chance to be with our people, all of which is good within reason, that we do not graduate to a deeper, truer faith. On that note, then, I suspend the halaqas, in the hopes that we all spend more time in worship; learning is vital, but learning without action is ultimately futile.

Except yesterday morning, one of my high school students messaged. “Do we have halaqa today?”

With a smile on face, I typed back that while we don’t have halaqas in Ramadan, I’d be open to our meeting — mind you, we end our classes an hour before sundown — if enough students really wanted to learn. The onus was on them to convince at least half of their cohort to show up for a class that ends an hour before maghreb, when they’d be at their hungriest, on a Sunday evening.

The Joke Was On Me

While only half of them could make it, more of them wanted to (some had previously committed, didn’t have rides, that kind of thing.) At that point, what was I going to do—say no so on the Day of Judgment I could have a free, pleasant Sunday afternoon in Ramadan count against me.

I took our unexpected halaqa in the direction of this post: To talk about how disaffected many Muslims were by the early tragedies of our history, provocations that pushed and reminded them (and should instruct us) that wealth and power neither suffice nor serve our purpose. Our intent is God; we got into philosophy, theology, Sufism and Salafism, questions of accountability and structures of piety.

I have to be honest, it was a beautiful part of the day. I was surprised (in the very best way) they wanted to meet and even more excited by how happy they were to go over the usual hour, because they had some big questions.

Call it an early Eid gift: This was the young men who’d asked for a class, but each and all of the students I teach are wonderful. I enjoy spending this time with them.

In pushing me, I’m kept on my toes, too.

Ramadan v Ramadan

I often don’t plan out the next halaqa until the most recent one has been completed; their responses, questions and reflections help me understand which direction to go in next. Very much like Sunni Islam itself, which evolved as a tandem between top-down scholarship and bottom-up piety, and retains that nuanced checks-and-balances approach, I try to do the same.

What I want to teach + what they want to learn =

So what will I teach next?

I might talk to them about the iftar (break-fast) dinner I attended immediately after the halaqa: The Islamic Center of Mason last night hosted a meal with our neighbors, fellow Masonians (if that’s the demonym) from all walks of life: doctors, executives, entrepreneurs, younger and older, recent immigrants and longtime residents, a simple, beautiful and wholesome chance to meet each other—and learn about our city.

I’d encourage my students and my readers to share Ramadan with others—not in an instrumental sense, mind you, not because we want something out of them, but because we want to introduce ourselves, share what matters to us, and invite others to open themselves up. That kind of engagement is real, genuine, sincere and part of what our country needs right now.

Others can benefit from knowing us. We can certainly benefit from knowing them! Just at our table, one of the students in attendance secured a summer internship opportunity, the kind of opening that comes when you’re… well, open.

That’s not all I could talk to my students about for the next halaqa, though.

I might talk to them about a decision I’ve made, that once seemed so hard, but now seems so obvious. You see, because of reasons I’ve outlined here before, I find it hard to sleep after fajr. But I also feel guilty when I don’t attend taraweeh, when I don’t make time for Ramadan in the ways I’d grown accustomed to. Except I’m not who I was when I was fifteen or even thirty.

My obligations and my routines mean I’ve been increasingly fatigued through recent Ramadans, running on fumes by the end of the month; when the last ten nights came, I’d be a wreck, falling asleep when I’d hoped to have more time in worship.

But am I not responsible for my time? Am I helpless? I sit around telling the students we should challenge ourselves in sustainable ways, that growth comes through wisdom, moderation and balance, but I was breaking myself. Since I am an adult, responsible for my life and my well-being, I’ve decided to try something different. I’ll be going to bed every night, God willing, after ‘isha and even on the last nights.

Inshallah.

If I sleep early enough, I find it very easy to wake up before fajr. We all have different clocks and capacities after all: Some folks can stay up late and sleep in. That doesn’t include me. I should take a page from my own curricula and lean into the opportunities God gives commensurate with the obligations I have, to family, to kids, to myself. The last third of the night, for example, is a very special time.

So is the hour before iftar. Take what you can!

Why am I telling you this? Because if I talk about it here, I have to hold myself to it, and because I hope you teach Islam this way, too: God is giving us multiple means to stay close to Him, to be in His shade and His love and His mercy. Find ways to find God in the ways that strengthen you, yes, but do not crush you. Because we have only so much time. Don’t make it your enemy. Make it your friend.

A Harder Lesson

On that note, there’s something else I want to go back to, too, especially for the young men in these halaqas.

I’d like to find a way to work in the underlying lesson behind this powerful essay by Mark Oppenheimer, whose Substack I’d not previously read. He makes a strong case, which echoes Ramadan too. Why are we here in the world, where we are and as we are? What are we to do with the blessings God gives us? How do we give of the gifts we do not deserve? For men, that includes our strength. That includes our family.

Be careful therefore who we valorize. Who we take from. What we idolize.

One of my students once brought up one of the manosphere men (if you know who I mean, and I’m sure many of us do). I let him make his full point and then I asked him a simple question: “Do you think this man models our faith?” He was quiet, unsure, looking for a talking point, at which point I followed up — before the entire halaqa — “would you think such a man would be a good husband and a good father?”

“Would you want a man like that to be your father?”

The enthusiasm quickly disappeared. “Would you want a man like that to be married to your mother?”

I pivoted to the topic we’d been discussing that week—how we keep our community strong. Each of you, I told them, has a duty to uplift this ummah. We are a small faith in a big and shining sea. Without parents who give their all, which one day includes all of you, we aren’t likely to build. We’re going to lose people. You can’t make someone Muslim. But you can make it more likely or less likely they’ll want to be.

Who we are at home says a lot about who we are in the world. And who we are in the world, in turn, tells us what comes and doesn’t come out of that home. I know every parent and stepparent wishes they could do more. We all make mistakes. But that doesn’t let any of us off the hook. What are we willing to give up? Who do we want these kids to be? My parents crossed the sea, and yet another sea, for me.

With what they gave me, I hope to give back. That’s part of gratitude. Other men take what they have and, worse, what others have built, and destroy. If they are strong, it’s because of what others accomplished. They do not contribute. They use, abuse, consume, exhaust and diminish. We will not be enriched by them. But we must do more than point this out. We must build and sustain an alternative.

From The Sea to the Shining Sea

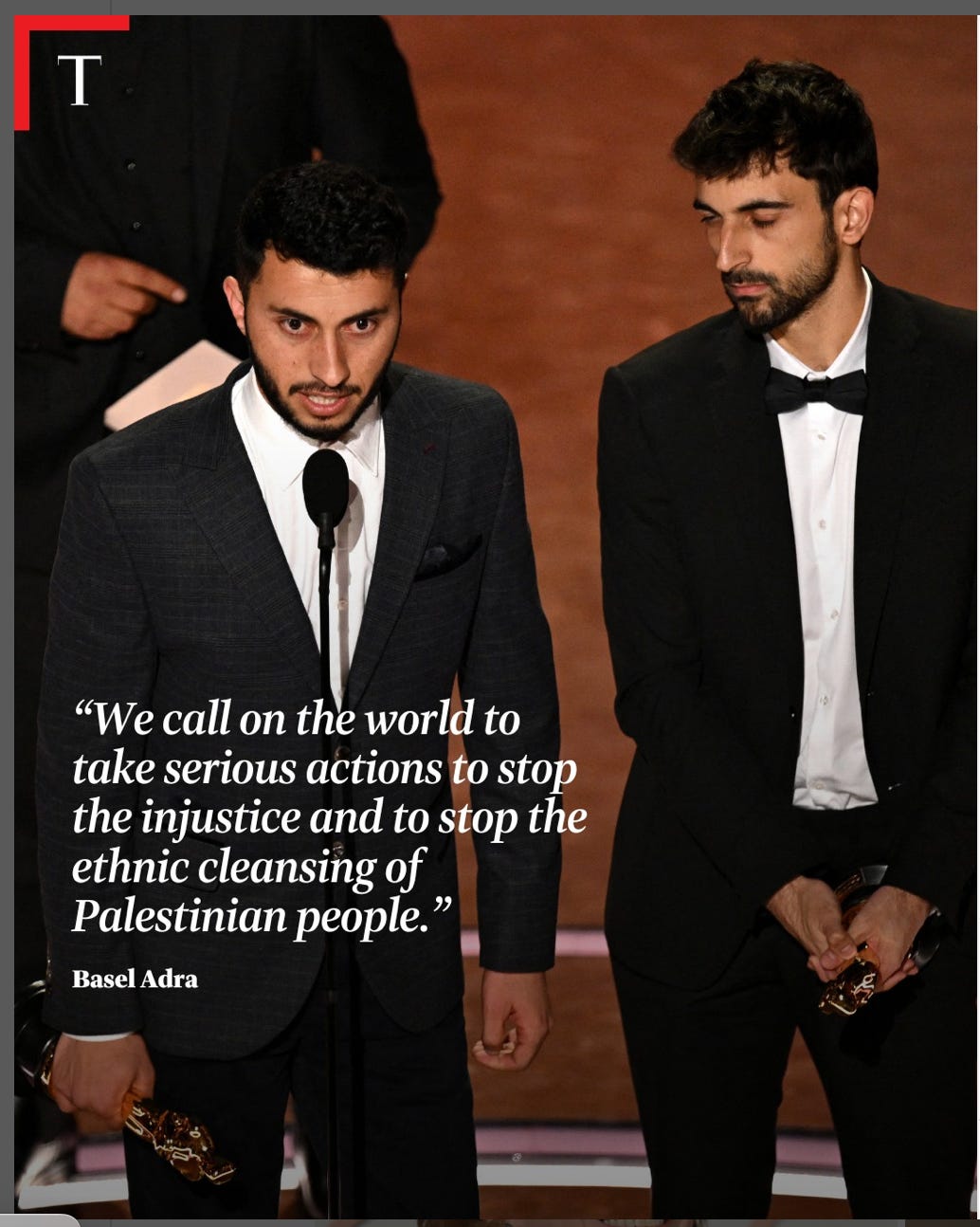

Last night, as you’ve probably heard, a documentary film about Palestine that was so “controversial” it could not be distributed except independently won an Oscar! It’s called “No Other Land”; we’ve got a Vice President berating democracies for free speech while funding dictatorships and war crimes, because the only subject that’s consistently censored in America on right and left might just be the most egregious moral tragedy of our time. This one.

Time Magazine shared this image with their 12.4 million Instagram followers.

Still, the win isn’t just good news, but a beautiful reminder in bleak moments: There’s a lot of people in our country who do care—and a lot more who don’t know what’s happening and would care if they so knew.

If we’re not out there, engaging, serving, and supporting our fellow Masonians, Ohioans, Americans—we’re not doing what God asks (and believe me, He will ask, and we don’t want to be fumbling for an answer on that day)… we’re not being good neighbors, good citizens, good Muslims. It’s easy to check out. Given the news these days, I wouldn’t blame you.

But is that really what God asks of us?

I love the idea of sharing faith, culture, expertise, food. We have some great cuisines from the parts of the world many of us are from. In fact, yesterday the Islamic Center of Greater Cincinnati hosted a bursting Ramadan bazaar, so busy the parking lot had no spaces left, and my wife and our middlemost attended, picking up lots of Ramadan gear — expect a Substack soon with specifics! — including a gift for me.

It’s so good, I’m telling you right now—buy this for yourself. But not just you.

Eid Mubarak For Your Beard

Olivology is the brand. We got candles for the house. Candles for friends and neighbors. And for me? Their Hair + Beard Oil. While I love my beard, my beard requires love, too. This is that. I’m going to buy more and I’m telling all the men here to get themselves some, too.

Check out Olivology for everything else they have, too.

If you’re looking for something sweet, a treat for the upcoming Eid or, really, just any occasion, and I’m saying this as someone who’s had some fantastic cookies in my life… Aydin’s are incredible. M&Ms? Awesome. Brown butter toffee chocolate chip? Possibly heaven. Brown butter Nutella? Approximating firdaws on our limited plane.

There’s a new cookie, too—karak, as in the type of chai. I’ve not tried those, but they did sell out fast. I believe in the wisdom of the cookie crowd.

In both cases, you get to support young entrepreneurs emerging here in Cincy.

Ramadan kareem, brother Haroon. Are you looking for product endorsements on Substack? LOL